29

Jan,2026

29

Jan,2026

Leukemia and Lymphoma: Targeted and Cellular Therapies

Twenty years ago, a diagnosis of relapsed leukemia or lymphoma often meant a grim outlook. Chemotherapy was the only real option, and it came with brutal side effects-hair loss, nausea, fatigue, and a high chance of the cancer coming back. Today, that story is changing. For many patients, the fight against blood cancers is no longer about surviving chemotherapy, but about choosing between powerful new tools: targeted therapies and cellular therapies. These aren’t just upgrades-they’re revolutions.

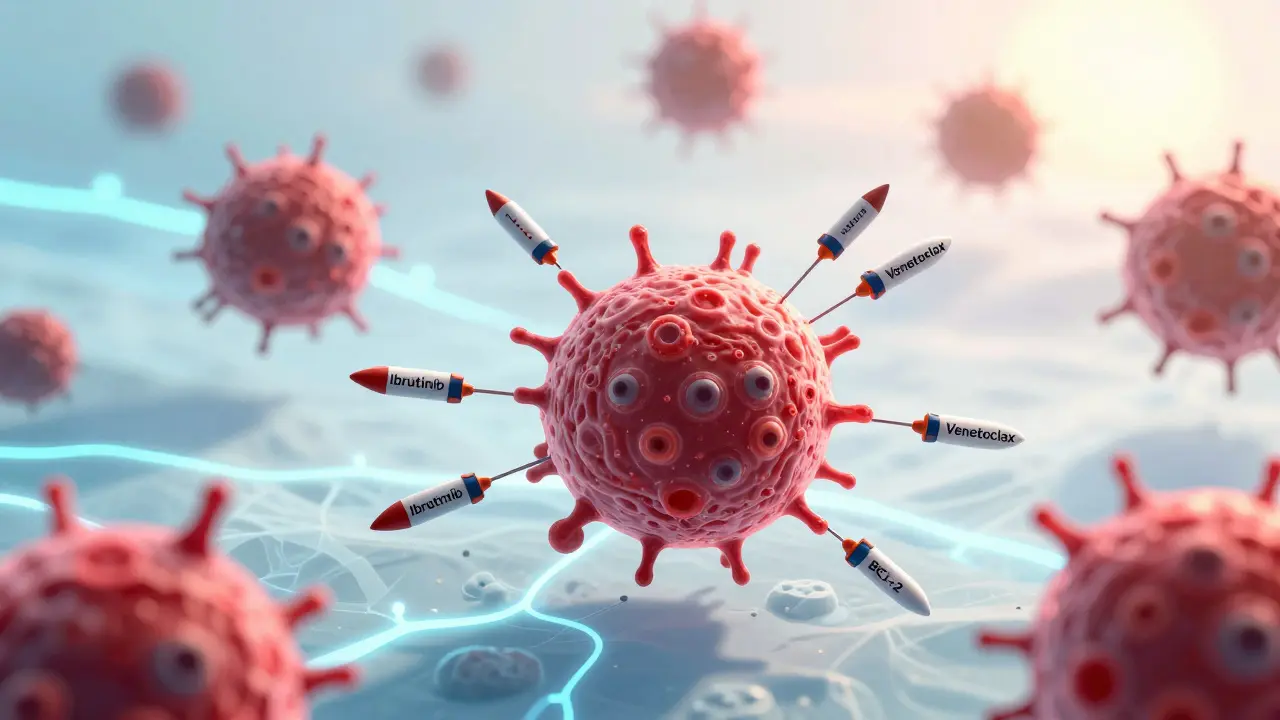

Targeted therapies attack cancer at its molecular roots. Instead of poisoning every fast-growing cell in the body, they zero in on specific proteins that cancer cells depend on to survive. Think of it like cutting the power to a single machine in a factory, rather than shutting down the whole plant. One of the first breakthroughs came in 2001 with imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. It turned a once-deadly disease into a manageable condition for most patients. Since then, drugs like ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and venetoclax have become standard for many types of leukemia and lymphoma.

Ibrutinib, sold as Imbruvica, blocks a protein called Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK), which B-cell cancers need to grow. Patients take it as a daily pill-420 mg once a day-with few of the harsh side effects of chemo. Venetoclax (Venclexta) works differently. It targets BCL-2, a protein that keeps cancer cells alive even when they should die. It’s given orally too, but it requires a slow ramp-up over five weeks to avoid tumor lysis syndrome, a dangerous drop in electrolytes caused by rapid cancer cell death. These drugs are now used in combinations, like venetoclax with obinutuzumab or ibrutinib, giving patients deep, lasting remissions without needing lifelong treatment.

But the most dramatic shift came with cellular therapy. CAR T-cell therapy takes your own immune cells and turns them into living drugs. Here’s how it works: First, doctors collect your T cells through a simple blood draw called leukapheresis. Then, in a lab, those cells are genetically modified to carry a special receptor-the chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR-that lets them recognize and kill cancer cells. The cells are multiplied, sometimes into the billions, then infused back into your body. Once inside, they multiply again and hunt down cancer like guided missiles.

The first CAR T-cell therapy approved was tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) in 2017 for kids with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Since then, others like axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) and lisocabtagene maraleucel (Breyanzi) have joined the list. They’re used mostly for patients who’ve tried other treatments and failed. And the results? Stunning. In relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma, one CAR T-cell therapy showed a 100% response rate and an 88% complete remission rate. For some patients, it’s the first time in years their cancer has vanished.

But these therapies aren’t without risks. About 20 to 40% of patients experience cytokine release syndrome-a flood of immune chemicals that can cause high fever, low blood pressure, and trouble breathing. Neurotoxicity is another concern: confusion, seizures, or trouble speaking can happen within days of infusion. That’s why CAR T-cell therapy is only given in specialized centers with ICU access. Hospitals need trained teams, 24/7 monitoring, and protocols to handle these side effects. It’s not something a local clinic can offer.

Cost is another hurdle. A single CAR T-cell treatment can run between $373,000 and $475,000. Even with insurance, patients may face $15,000 to $25,000 in out-of-pocket costs per month for targeted therapies. That’s why many doctors worry about access. In the U.S., 89% of National Cancer Institute-designated centers offer CAR T-cell therapy, but only 32% of community hospitals do. Rural patients often travel hundreds of miles-or skip treatment entirely.

And then there’s the question of who benefits most. Not everyone responds. Patients with del(17p) or TP53 mutations tend to develop resistance faster to BTK inhibitors. For them, CAR T-cell therapy may be the better option. But even CAR T isn’t perfect. Some cancers escape by losing the target antigen-like CD19. That’s why new therapies are coming. Gilead’s KITE-363 and KITE-753 are dual-target CAR T-cells that attack both CD19 and CD20 at the same time. Early data shows they lower the chance of relapse and may be safer, possibly even usable outside the hospital in the future.

Doctors are also pushing to use these therapies earlier. Right now, CAR T-cell therapy is usually a last resort. But in 2025, a survey of hematologists found 68% believe it should become a first-line option for high-risk lymphoma patients by 2030. Why? Because the long-term survival data is improving. In a major trial called ZUMA-7, patients with large B-cell lymphoma who got Yescarta as second-line treatment had a 42.6% four-year survival rate-far better than those who got chemo again.

Targeted therapies, on the other hand, are changing the natural course of disease. Before these drugs, patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) often developed Richter transformation-a rare but deadly shift into aggressive lymphoma-within 2 to 2.5 years. Now, that window has stretched to nearly five years. The cancer still progresses, but slower. And for many, it’s not just about living longer. It’s about living better. No hospital stays. Fewer infections. More time with family.

Still, challenges remain. Resistance to targeted drugs is inevitable. Most patients on ibrutinib or acalabrutinib relapse within 3 to 5 years. And while CAR T-cell therapy can cure some, we don’t yet know how many. Long-term side effects-like weakened immunity or chronic fatigue-are still being studied. And the cost? It’s unsustainable if we don’t find ways to make these therapies cheaper and more widely available.

What’s next? Researchers are working on off-the-shelf CAR T-cells-made from donor cells, not your own-that could be given like a blood transfusion. There are also new drugs targeting different proteins, like BCL-xL and MCL-1. And combinations are being tested: CAR T-cell therapy followed by a targeted drug to keep the cancer in check.

For patients today, the message is clear: you’re not stuck with the old options. There are choices. And for some, those choices mean a real chance at long-term remission-or even cure.

How Targeted Therapies and CAR T-Cell Therapies Compare

| Feature | Targeted Therapies (e.g., Ibrutinib, Venetoclax) | Cellular Therapies (e.g., Yescarta, Kymriah) |

|---|---|---|

| How it works | Oral drugs that block specific cancer proteins | Infusion of genetically modified patient T cells |

| Administration | Daily pill, outpatient | Single IV infusion, hospital stay required |

| Time to treatment | Days to start | 3-5 weeks to manufacture cells |

| Common side effects | Diarrhea, bruising, fatigue, low blood counts | Cytokine release syndrome, neurotoxicity, prolonged low blood counts |

| Duration of effect | Continuous treatment needed; resistance develops in 3-5 years | Potentially permanent; one-time treatment with lasting immune memory |

| Best for | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), mantle cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma | Relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphomas, pediatric ALL |

| Cost per treatment | $10,000-$25,000/month | $373,000-$475,000 |

| Approval status (as of 2025) | Multiple FDA-approved for CLL, SLL, MCL | Approved for DLBCL, follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, ALL |

Who Benefits Most From Each Therapy?

Not every patient is a candidate for every treatment. Your age, cancer type, genetic mutations, and prior treatments all matter.

For patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), targeted therapies are now the first choice. If you’re newly diagnosed and have no high-risk mutations like del(17p), a combination of venetoclax and obinutuzumab can give you a fixed 12-month course with deep remissions. You can stop treatment after a year and live without daily pills for years.

But if you’ve already tried a BTK inhibitor like ibrutinib and your cancer came back, venetoclax might be next. If you’ve failed both, CAR T-cell therapy becomes your best shot. Studies show that even patients who’ve had multiple relapses can achieve complete remission with CAR T-cells.

For aggressive lymphomas like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the path is clearer: if you relapse after two rounds of chemo, CAR T-cell therapy is now the standard. ZUMA-7 data showed it doubled the chance of survival compared to another round of chemo.

Patients with mantle cell lymphoma who’ve relapsed after a BTK inhibitor and chemo are now being offered CAR T-cell therapy as a bridge to transplant-or even as a standalone cure. New dual-target CAR T-cells are showing even better results, with remission rates over 60% in early trials.

But for older patients with multiple health problems, the risks may outweigh the benefits. CAR T-cell therapy can be too intense. Targeted therapies, with their lower toxicity, may be a better fit-even if they’re not as powerful.

What Happens When Treatment Stops Working?

Resistance is the biggest challenge in blood cancer treatment today. With targeted therapies, cancer cells learn to adapt. They might mutate the BTK protein so ibrutinib can’t bind to it. Or they might turn on a backup survival pathway. That’s why some patients on ibrutinib relapse after just two years.

For CAR T-cell therapy, the problem is different. Sometimes, the cancer cells stop making the target antigen-like CD19. If the CAR T-cells can’t find their target, they can’t kill the cancer. That’s why researchers are developing CARs that target two antigens at once. Early results suggest this reduces relapse rates by nearly half.

When targeted therapies fail, the next step is often switching to another drug. For example, moving from ibrutinib to acalabrutinib, or adding venetoclax. But once you’ve tried both BTK and BCL-2 inhibitors, options shrink fast. That’s where clinical trials come in. New drugs targeting proteins like MCL-1 or PI3K are showing promise.

For CAR T-cell failure, options are limited. Some patients get a second CAR T-cell infusion, but success is rare. Others turn to stem cell transplants. But the most exciting frontier is “off-the-shelf” CAR T-cells-made from healthy donors-that could be given again if the first one fails.

What to Expect During Treatment

If you’re starting targeted therapy, you’ll likely take a daily pill at home. You’ll need blood tests every few weeks to check your counts and liver function. Side effects like diarrhea, muscle pain, or bruising are common but usually mild. Your doctor will adjust the dose if needed.

For venetoclax, the first five weeks are critical. Your dose starts low and increases weekly. You’ll probably be hospitalized during this ramp-up to watch for tumor lysis syndrome. After that, you can take it at home.

For CAR T-cell therapy, the process is longer. First, you’ll have a leukapheresis appointment to collect your T cells. Then you wait 3 to 5 weeks while they’re engineered. During that time, you might get bridging therapy to keep the cancer under control.

When the cells are ready, you’ll have a short hospital stay. You’ll get chemotherapy to clear space for the new cells, then the CAR T-cell infusion. You’ll stay in the hospital for at least a week. Doctors will watch for fever, low blood pressure, confusion, or seizures. If you have cytokine release syndrome, you’ll get tocilizumab or steroids. Neurotoxicity is treated with seizure meds and close monitoring.

After discharge, you’ll need weekly visits for the first month, then monthly for six months. Your immune system will be weak. You’ll need to avoid crowds, get vaccines, and take antibiotics to prevent infections.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are targeted therapies better than chemotherapy for leukemia and lymphoma?

Yes, for most patients with chronic or relapsed disease. Targeted therapies have fewer side effects, can be taken at home, and often work better than chemo. For example, in CLL, combinations like venetoclax plus obinutuzumab lead to longer remissions than older chemoimmunotherapy regimens. But chemo is still used in aggressive, fast-growing cancers where quick, powerful action is needed.

Can CAR T-cell therapy cure lymphoma?

For some patients, yes. In relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma, about 40% of patients treated with Yescarta remain in remission at four years. That’s considered a functional cure. The CAR T-cells stay in the body and keep fighting cancer cells that try to return. But not everyone responds, and some relapse later. Long-term data is still being collected.

Why is CAR T-cell therapy so expensive?

Because it’s personalized medicine. Each treatment is made from the patient’s own cells, requiring a complex, labor-intensive process in a sterile lab. It includes cell collection, genetic engineering, expansion, testing, and delivery-all under strict FDA regulations. The cost also covers the hospital stay, managing side effects, and long-term follow-up. Some insurers are starting to negotiate lower prices, but it remains a major barrier.

Do I need to go to a big hospital for these treatments?

For targeted therapies, no. You can take pills at home with regular check-ins. But CAR T-cell therapy requires a certified center with ICU capabilities, trained staff, and experience managing cytokine release syndrome. Only about one-third of community hospitals offer it. If you live far from a major center, you may need to relocate temporarily.

What’s the future of these therapies?

The future is earlier use and smarter combinations. By 2030, CAR T-cell therapy may become a first-line option for high-risk lymphoma patients. New dual-target CARs, off-the-shelf versions, and drugs that block resistance pathways are in development. The goal isn’t just to treat cancer-it’s to make it a chronic, manageable condition-or eliminate it entirely.

Next Steps for Patients and Families

If you or a loved one has been diagnosed with leukemia or lymphoma, ask your oncologist these questions:

- What genetic mutations does my cancer have? (This determines if targeted therapy will work.)

- Have I tried all standard treatments? If not, what’s next?

- Am I a candidate for CAR T-cell therapy? If so, where is the nearest certified center?

- What are the costs, and does my insurance cover these therapies?

- Are there clinical trials I should consider?

Don’t wait to ask. These therapies are changing survival rates-but only if you know they exist. Talk to your doctor, seek a second opinion, and connect with patient advocacy groups like the CLL Society or Lymphoma Research Foundation. You’re not alone in this fight.

I've seen patients go from bedridden to hiking in the Rockies after CAR T. It's not magic, but it's close. The side effects are scary, yeah, but so is watching someone fade away on chemo. I work in oncology nursing. This is the first time I've seen real hope in a decade.

America still leads in this shit. China? Russia? They're still stuck in the 90s with chemo. We got the brains, the tech, the $$$ to make this happen. Don't let the Europeans tell you otherwise. 🇺🇸

The ontological shift in therapeutic paradigms cannot be overstated. We have transitioned from a mechanistic model of cytotoxic obliteration to a phenomenological engagement with the immune system as an autonomous, adaptive agent. This is not merely medical advancement-it is epistemological reconfiguration.

They don't want you to know this but the FDA is in bed with Big Pharma. These 'miracle' drugs are just expensive placebos to keep you hooked. Your immune system gets wrecked, you pay $50k/month, and they sell you more pills. The real cure? Fasting and turmeric. But that doesn't make them rich.

In India, we have a different reality. My cousin in Delhi was told he needed CAR T but the nearest center is in Mumbai, 1500 km away, and the cost is 30 times his annual income. We have no insurance, no government support. So we waited. He passed last month. This is progress? Only if you live in a penthouse in Manhattan.

The cost is obscene. $475,000 for one treatment? That’s more than the median household income in 47 states. This isn’t medicine-it’s a luxury good for the wealthy. We’ve turned healthcare into a casino where the house always wins.

My mom did venetoclax and it was rough at first but she’s been off it for 18 months now and just went on a cruise. No hair loss. No vomiting. Just pills. I’m so glad they didn’t just throw chemo at her again

Bro, I just read this and I’m crying 😭 My uncle in Jaipur had CLL and we thought he was gone. Then we found a trial with venetoclax-paid out of pocket for 6 months. He’s alive. He’s coaching kids in cricket now. This is real. This is hope. Don’t give up. 🙏

We treat cancer like a problem to be solved when perhaps it is a mirror. A reflection of our industrialized lives, our toxins, our disconnection from nature. The drugs are brilliant but they are symptoms of a deeper illness-the illness of believing we can engineer our way out of everything

I know someone who got CAR T and now she’s got a dog and a garden and she paints every day. I just think its so beautiful that science can give someone back their quiet life

The entire paradigm is predicated on a reductionist model of oncogenesis that ignores the systemic, epigenetic, and microbiome-mediated etiologies of hematologic malignancies. By focusing exclusively on CD19 and BTK, we are engaging in therapeutic myopia-a myopia that is economically incentivized by the pharmaceutical-industrial complex’s patent-driven innovation matrix. The future lies in multi-omic, AI-driven, context-aware therapeutic landscapes-not single-target monoclonal myopia.

The data on long-term immune reconstitution post-CAR T remains incomplete. While response rates are impressive, the durability of B-cell aplasia, the risk of secondary malignancies, and the impact of chronic immune dysregulation over a 15- to 20-year horizon are not yet fully characterized. Caution is warranted in declaring victory.