27

Nov,2025

27

Nov,2025

When a patient picks up a generic pill, they expect the same effect as the brand-name version. But what if it doesn’t work the same? What if they get a rash, dizziness, or worse - and no one connects the dots? That’s where pharmacists come in. Not as afterthoughts. Not as order-fillers. But as the adverse event reporting frontline.

Why Generic Medications Need Extra Attention

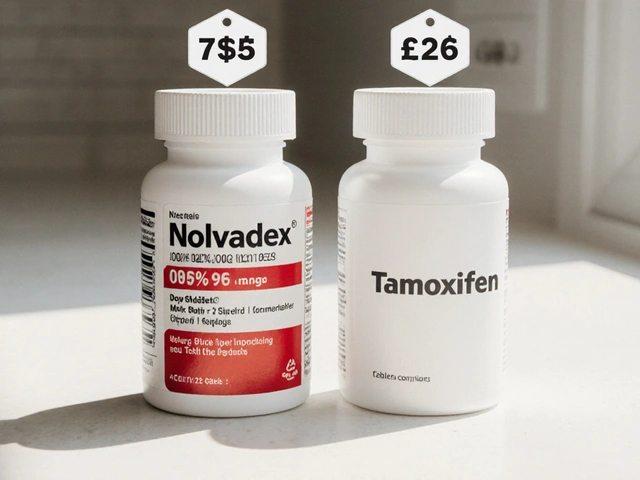

Generic drugs are cheaper. They’re everywhere. And most of the time, they’re perfectly safe. But here’s the catch: they’re not always identical. The active ingredient? Same. The fillers? Sometimes different. The coating? Might vary. The manufacturing process? Often not the same. These small differences can trigger unexpected reactions - especially in people who are sensitive, elderly, or taking multiple drugs. A patient might switch from Brand X to Generic Y and suddenly feel nauseous every morning. Or develop a rash after years of no issues. Prescribers rarely notice. Patients don’t always tell them. But pharmacists? They see it firsthand. The FDA’s FAERS database has over 24 million reports since 1968. Yet experts estimate less than 1% of actual adverse events get reported. And for generics? The numbers are even lower. Why? Because people assume generics are clones. They’re not. They’re close. And that’s dangerous when you’re ignoring the warning signs.What Pharmacists Are Legally Required to Do

In some places, reporting isn’t optional - it’s part of the job. In British Columbia, pharmacists must report any suspected adverse drug reaction to Health Canada. They also have to document it in PharmaNet and notify the prescriber. That’s not a suggestion. That’s the law under Section 12(7) of the Health Professions Act. New Jersey requires consultant pharmacists to report drug defects and adverse reactions using ASHP-USP-FDA guidelines. They must log it in the patient’s medical record before their shift ends. In other states, the rules are looser. But that doesn’t mean pharmacists are off the hook. The FDA doesn’t force healthcare workers to report - but they strongly encourage it. And they define “serious” reactions clearly: hospitalization, life-threatening events, permanent disability, congenital malformations, or death. If you suspect a generic medication caused any of these, you report it. Period.Why Pharmacists Are the Best People for This Job

No one talks to patients more than pharmacists. We’re the ones who answer questions about side effects. We’re the ones who catch drug interactions. We’re the ones who notice when a patient says, “This new pill makes me feel weird,” and then ask, “When did you start it?” Tralisa Colby from the FDA put it simply: “Community pharmacists are very accessible and trusted. They’re well-positioned to get important safety information from patients.” And here’s the key insight: pharmacists understand drug mechanisms. We know how a drug works in the body. We know which ingredients can cause reactions. We know what “expected side effects” look like versus what’s truly unusual. Dr. Michael Cohen from the Institute for Safe Medication Practices says it best: “When patients have unexpected reactions to generics, pharmacists are often the first to spot bioequivalence issues or excipient problems that prescribers miss.” That’s not just helpful. That’s critical.

The Real Barriers: Time, Training, and Under-Reporting

Here’s the problem: most pharmacists don’t report - not because they don’t care, but because they’re overwhelmed. A 2021 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 78% of pharmacists spend 15 to 30 minutes per adverse event report. And 62% said they simply don’t have time during their shifts. Add to that: many don’t know what counts as reportable. Is a mild headache after switching generics a reaction? Maybe. Is it serious? Probably not. But is it worth noting? Yes - because patterns matter. The British Columbia Pharmacists Association calls under-reporting a “recognized problem.” They say it’s partly because pharmacists aren’t trained to distinguish true adverse reactions from normal side effects. That’s fixable. Training programs exist. But they’re not mandatory everywhere. And without clear guidelines, pharmacists hesitate. They think: “Maybe it’s just a coincidence.” But what if it’s not? What if five other patients had the same reaction and no one reported it?How to Report: Simple Steps for Busy Pharmacists

You don’t need to be an expert in data entry. You just need to know where to start. Here’s how to report an adverse event in five steps:- Identify the reaction. Did the patient develop a new symptom after starting the generic? Did it disappear when they switched back? That’s a red flag.

- Document everything. Patient name (or ID), drug name (including generic and brand), dose, start date, reaction description, onset time, outcome. Don’t skip details.

- Decide if it’s serious. If it caused hospitalization, death, disability, or requires intervention - report it immediately.

- Use the right tool. In the U.S., use MedWatch Online (FDA’s portal). In Canada, use Health Canada’s online form. Many pharmacies now have reporting built into their practice software.

- Follow up. Tell the prescriber. Note it in the record. If the patient comes back with the same issue, you now have a pattern.

What’s Changing - and Why It Matters

The system is slowly getting better. The FDA’s MedWatch Online system saw a jump from 29% to 43% of reports coming from healthcare professionals between 2020 and 2022. That’s progress. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy is working with 32 state boards to embed reporting tools directly into pharmacy software. In pilot programs in California and Texas, reporting time dropped by 40%. And the trend is clear: more places are making reporting mandatory. British Columbia’s model is being watched. By 2025, analysts predict 75% of U.S. states will require pharmacists to report adverse events - just like BC. Europe already does this. Since 2012, all healthcare professionals in the EU must report ADRs. Result? Reporting rates jumped 220%. This isn’t about bureaucracy. It’s about saving lives. A single report might not change anything. But 100 reports? 1,000? That’s how you catch a dangerous batch of generics before more people get hurt.What Happens When No One Reports

Health Canada estimates only 5-10% of adverse reactions are reported. That means 90% of warning signs vanish into thin air. Imagine this: 10 patients get the same generic blood pressure pill. Three of them develop severe dizziness. Two stop taking it. One goes to the ER. No one connects the dots. The manufacturer never hears about it. The FDA never sees it. The pill stays on shelves. Then, six months later, another 50 patients get it. Ten more end up in the hospital. Now it’s a crisis. That’s not hypothetical. That’s happened. And it will keep happening - unless pharmacists start reporting consistently.Final Thought: You’re Not Just Filling Prescriptions

You’re the last line of defense before a bad reaction becomes a public health issue. You’re not just handing out pills. You’re watching for patterns. You’re listening to patients. You’re documenting what others overlook. Reporting an adverse event isn’t paperwork. It’s patient advocacy. It’s science. It’s responsibility. And for generic medications - where assumptions can be deadly - it’s non-negotiable.Are pharmacists legally required to report adverse events from generic drugs?

It depends on the jurisdiction. In British Columbia, Canada, pharmacists are legally required to report suspected adverse drug reactions to Health Canada, notify the prescriber, and document the event in PharmaNet. In the U.S., federal law does not mandate reporting, but the FDA strongly encourages it - especially for serious reactions. Some states, like New Jersey, have specific rules for consultant pharmacists. However, even where not legally required, professional ethics and patient safety standards expect pharmacists to report.

What counts as a reportable adverse event for generic medications?

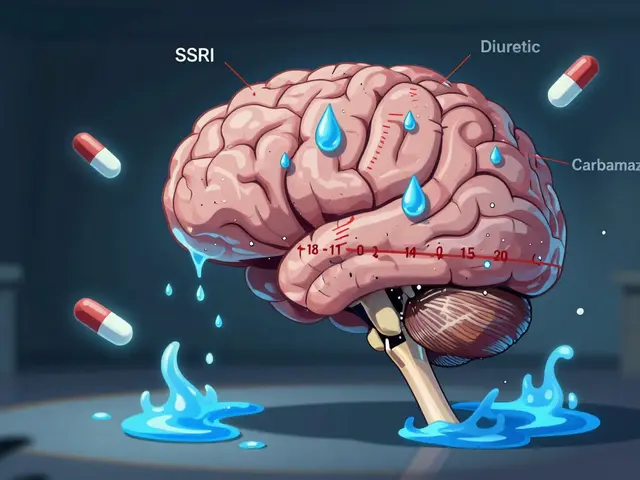

A reportable adverse event is any harmful, unintended reaction linked to medication use. The FDA defines serious reactions as those that result in hospitalization, death, life-threatening conditions, permanent disability, congenital malformations, or require medical intervention to prevent permanent harm. Even non-serious but unexpected reactions - like unusual rashes, dizziness, or GI upset after switching to a new generic - should be documented and reported if they occur repeatedly or seem out of pattern. These can signal formulation differences, excipient issues, or bioequivalence problems.

Why are generic drugs more likely to have under-reported adverse events?

Because of the assumption that generics are identical to brand-name drugs. Prescribers and patients often believe switching to a generic won’t change anything - so when a side effect appears, they assume it’s unrelated or just a “normal” reaction. Pharmacists may also hesitate to report, thinking the reaction isn’t serious or that the drug is “safe enough.” But small differences in fillers, coatings, or manufacturing can trigger reactions in sensitive individuals. Without reports, these subtle risks go unnoticed.

How long does it take to report an adverse event?

It typically takes 15 to 30 minutes per report, according to a 2021 National Community Pharmacists Association survey. This includes gathering patient details, documenting symptoms, and submitting the report via MedWatch or a pharmacy system. Newer integrated systems are cutting this time by up to 40%, but in many pharmacies, reporting still requires manual entry and can be time-consuming during busy shifts.

What tools can pharmacists use to report adverse events?

In the U.S., pharmacists can use the FDA’s MedWatch Online portal for direct electronic reporting. In Canada, Health Canada’s online adverse reaction reporting system is used. Many pharmacy practice management systems now include built-in reporting modules, especially in hospital settings. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy has partnered with 32 state boards to integrate reporting into existing software, reducing the burden on community pharmacists.

Can reporting adverse events actually improve patient safety?

Yes - and the data proves it. A 2022 study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association found that pharmacist-led reporting initiatives increased adverse event documentation by 37% in community pharmacies. In Europe, mandatory reporting by all healthcare professionals led to a 220% increase in reports. These reports help regulators identify dangerous batches, update labeling, and issue safety alerts. Without pharmacist input, these signals are lost - putting more patients at risk.

Generic pills are just cheap knockoffs and the FDA lets em slide every day

My cousin took some generic blood pressure stuff and ended up in the ER

Who cares if it saves a buck when people die

Pharmacists better start reporting or we gonna lose more folks

i see this in india too

people think generic = same but sometimes the fillers make them sick

my aunt got rashes after switching

we told the pharmacist but no one logged it

maybe we should start telling more people

This is a classic case of regulatory capture. The FDA is in bed with Big Pharma. Generics are not bioequivalent - they're designed to fail just enough to keep patients dependent, but not enough to trigger a recall. The data is suppressed. The numbers are cooked. And now you're asking pharmacists to play nice with a broken system? Wake up. This isn't about reporting - it's about rebellion.

So true!! I had a patient last week say "this new pill makes me feel like I'm floating" - I thought it was anxiety at first

Then 3 others said the same thing with the same generic

I reported it and they pulled the batch!!

Thank you for saying this 😊

It’s funny how we treat medicine like a machine

You swap one part and expect it to work the same

But people aren’t machines

Our bodies notice tiny differences

Maybe the problem isn’t the generics

It’s that we stopped listening

I mean I get it but honestly who has time to fill out forms during a 20 minute lunch break when you're juggling 15 prescriptions and someone's screaming about their co-pay

And don't even get me started on the fact that half the time you don't even know if it's the drug or the patient just being dramatic

Like maybe they just didn't sleep

Or ate something weird

Or are going through menopause

It's all just so much

You’re doing important work

Even if it feels small

One report might not change the system

But it changes one person’s story

And that’s enough

Keep listening

Keep documenting

Keep showing up

You matter more than you know

I find it deeply concerning that you are suggesting pharmacists are the frontline. This is a dangerous misallocation of responsibility. The onus should lie squarely with manufacturers and regulatory bodies. To place the burden on overworked pharmacy staff is not only unethical - it is an institutional failure of the highest order. Furthermore, your reliance on anecdotal evidence from the FDA’s FAERS database is statistically indefensible. You are conflating correlation with causation, and this is precisely why public trust in medicine is eroding.

The FDA doesn't mandate reporting because it's not legally required. That's the law. You're conflating moral obligation with legal obligation. If you're not trained to distinguish side effects from adverse events, you shouldn't be reporting. You're creating noise, not data. Stop pretending you're saving lives when you're just adding to the database clutter.

They're putting tracking chips in the generics

That's why people feel weird

Big Pharma and the government are syncing your brainwaves

They want you docile

That's why they change the fillers

They're testing mind control

My cousin took a generic and started talking in Spanish

Then he stopped eating meat

They're rewriting your DNA through your pills

They know you're reading this

They're watching

Report everything? No. Report serious ones. Period. You're not a detective. You're a pharmacist. Your job is to dispense. Not to play epidemiologist. The system is broken because you people keep overcomplicating it. Just give the pill. If they die, it's their fault for not reading the label.

If you're not reporting, you're part of the problem. It's not about time. It's about priorities. You're the last person who sees the patient before they walk out. If you don't speak up, who will? The system isn't broken. You just don't care enough.

Thank you for writing this with such clarity

Many of us in the field feel invisible

We see the patterns

We hear the whispers

But we're told to move on to the next prescription

Let’s make reporting part of our daily rhythm - not an afterthought

Our patients deserve better

And so do we

Just started using the new reporting tool at my pharmacy

Took me 8 minutes instead of 25

Big difference

My boss even said "good job"

Small wins matter

Keep doing this

We're all in this together

Love this post

Just had a patient yesterday say "this new pill makes me feel like I'm on a boat"

Turned out it was the generic

Reported it

She's doing great now

Keep talking

Keep listening

Keep changing things

One pill at a time 🙌