3

Jan,2026

3

Jan,2026

Side Effect Terminology Interpreter

Understand Common Postmarketing Side Effect Terms

Select a term below to see what it really means in the context of drug safety

Explanation

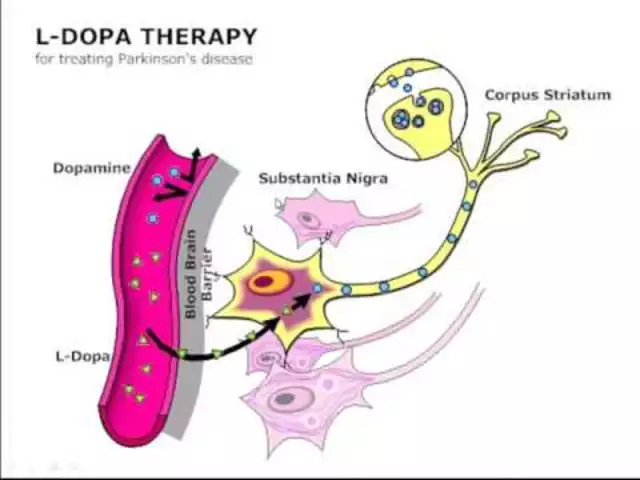

When you pick up a new prescription, the tiny print in the prescribing information isn’t just filler. It’s your last line of defense against hidden risks. One of the most confusing parts? The postmarketing experience section. You’ll find it in Section 6 of the drug’s full prescribing info, right after the clinical trial data. It lists side effects that showed up after the drug was already on the market - not in the controlled trials, but in real life, with hundreds of thousands of people using it. And here’s the thing: just because a side effect shows up here doesn’t mean it’s rare or harmless. It might be serious. It might be common. But you won’t know unless you understand what this section is really saying.

What Exactly Is Postmarketing Experience?

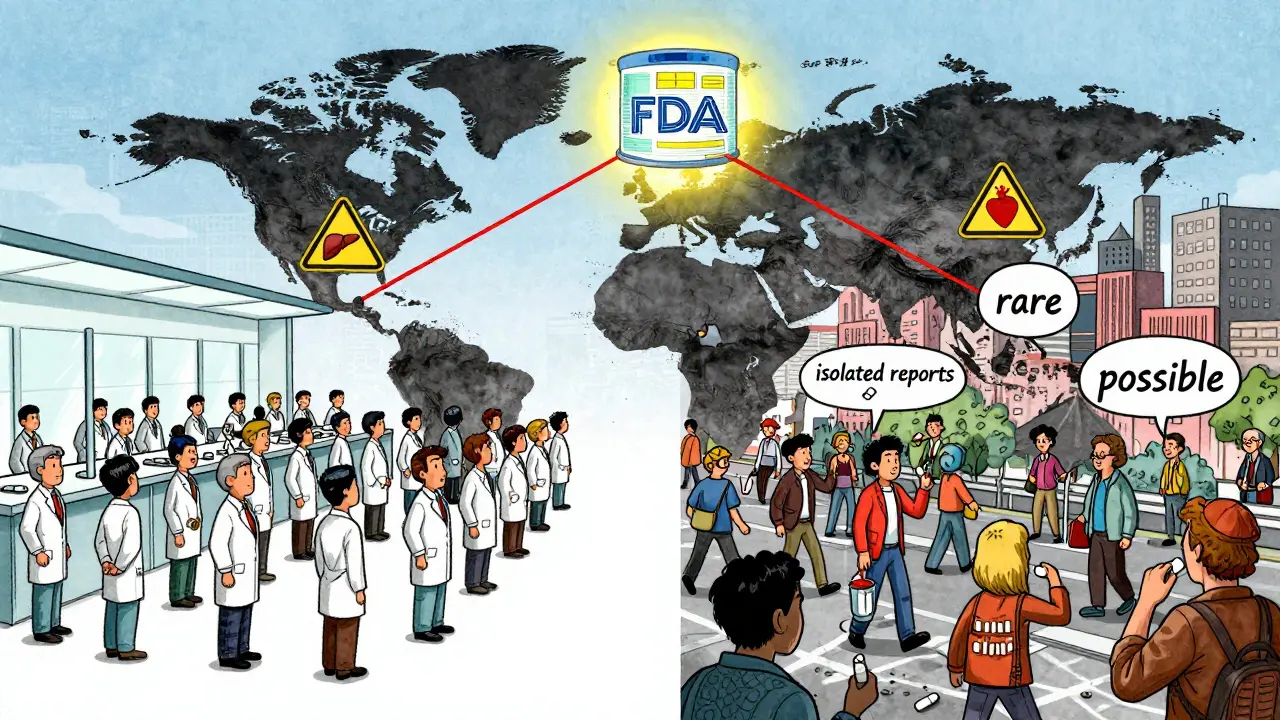

Postmarketing experience means what happens after the FDA approves a drug and it’s no longer just tested on a few thousand volunteers. It’s what happens when millions of people - with different ages, other health conditions, and other medications - start taking it. Clinical trials can’t catch everything. They’re too small, too controlled. A side effect that only happens in 1 out of 5,000 people? It’s almost impossible to spot in a trial of 3,000 patients. But once the drug hits the market, those rare reactions start showing up. That’s what the postmarketing section is for: to catch what the trials missed.

The FDA requires drugmakers to report any serious or unexpected side effects within 15 days of learning about them. These reports go into the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), which holds over 35 million reports as of 2023. That data gets reviewed, analyzed, and - if there’s enough evidence - added to the drug’s label. That’s how you get something like: “Isolated reports of liver failure” or “Cases of severe skin rash reported.”

Why the Language Is So Confusing

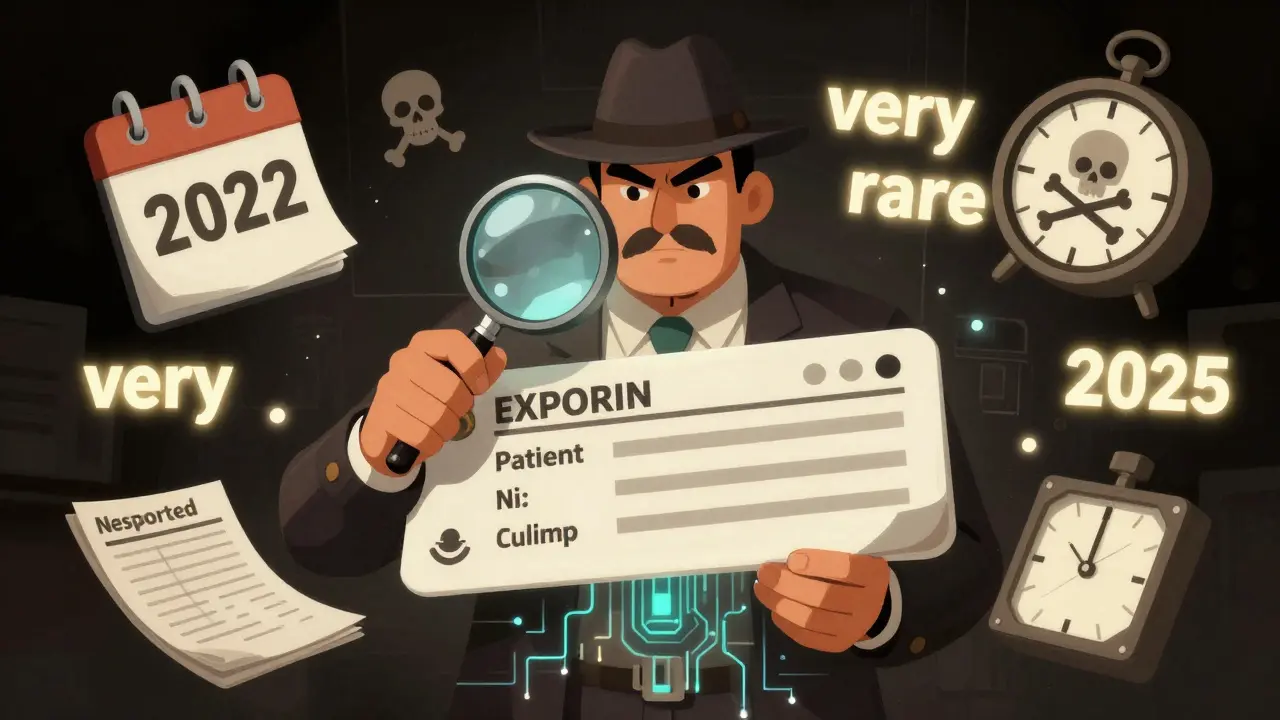

Look at this phrase: “Isolated reports of pancreatitis.” Sounds harmless, right? Like maybe one person had it, and it was a fluke. But here’s the truth: “Isolated reports” doesn’t mean “not serious.” It means “we don’t have enough data yet to say how often it happens.” In 2022, a new anticoagulant had 17 fatal bleeding events labeled as “isolated reports.” By the time the pattern was clear, it was too late for some patients. The language isn’t meant to downplay risk - it’s meant to reflect uncertainty. But doctors and patients often read it the wrong way.

Same with “reported cases.” That doesn’t mean the drug definitely caused it. It just means someone took the drug and then had the problem. Maybe it was a coincidence. Maybe it wasn’t. The FDA doesn’t confirm causation here - it just reports what was submitted. That’s why you’ll see qualifiers like “possible,” “suspected,” or “temporally associated.” These aren’t warnings. They’re red flags that say: “We’re watching this.”

Frequency Isn’t What You Think

Section 6.1 of the label lists side effects from clinical trials - the ones seen in the studies. Section 6.2 is where the postmarketing stuff goes. And here’s the trap: many clinicians assume anything listed only in 6.2 is less common or less dangerous. That’s wrong. A reaction listed in 6.2 might be rarer, but it could be far more serious. A 2021 study found that 78% of healthcare providers confused the two sections. One cardiologist on Reddit said he’d seen the same drug list the same side effect in both sections with different frequency estimates - and no one knew which one to trust.

The FDA uses standardized terms from MedDRA version 26.0 to describe frequency: very common (≥1/10), common (≥1/100 to <1/10), uncommon (≥1/1,000 to <1/100), rare (≥1/10,000 to <1/1,000), very rare (<1/10,000). But in postmarketing sections, those categories are often missing. Instead, you get vague terms like “occasional,” “rarely,” or “some cases.” That’s because the data isn’t precise enough. The number of reports doesn’t equal the number of actual cases - many go unreported. So when you see “rare,” it might actually be more common than it sounds.

What You Should Do When You See It

Don’t ignore the postmarketing section. Don’t assume it’s just noise. Here’s how to read it right:

- Look for severity, not just frequency. A “very rare” reaction that causes death or hospitalization is more important than a “common” one that causes a mild rash.

- Check if it’s unexpected. If a side effect isn’t listed in the clinical trial section but shows up here, it’s considered “unexpected.” That means it’s new information - and potentially a red flag.

- Watch for patterns. If you see the same reaction listed multiple times with different qualifiers (“isolated reports,” “some cases,” “a few instances”), it might be a signal the FDA is tracking.

- Ask: Is this biologically plausible? Does the drug’s mechanism make sense for causing this side effect? If yes, treat it seriously.

- Remember: absence isn’t safety. Just because a side effect isn’t listed doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen. The FDA says this outright: “The absence of a particular adverse reaction in the postmarketing section does not mean the drug does not cause the reaction.”

Why This Matters for Real Patients

Real-world stories show why this matters. A 2022 AMA survey of 1,247 doctors found that 63% were confused by how side effect frequencies were presented in postmarketing sections. Over 40% assumed reactions listed only in Section 6.2 were less serious. That’s dangerous. One pharmacist on ASHP’s forum described a case where a new diabetes drug was linked to severe hypoglycemia - labeled as “rare” in the postmarketing section. Three patients ended up in the ER before anyone realized it wasn’t rare at all - it was just underreported.

Patients aren’t immune to this confusion either. In the FDA’s 2021 Patient-Focused Drug Development initiative, 28% of 342 patient testimonials said they couldn’t understand the difference between side effects listed in trials versus those listed in postmarketing experience. Many thought “reported cases” meant “no big deal.”

How the System Is Changing

The FDA knows this system is flawed. That’s why they’re changing it. Starting January 2025, drugmakers must submit postmarketing data in a machine-readable format called SPL-ESD. That means computers can scan for safety signals automatically - not just humans reading dense text. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative already monitors 300 million patient records from hospitals and insurers. In 2022 alone, it generated over 1,200 active safety alerts.

AI is starting to help too. Pilot programs using artificial intelligence have predicted label changes with 83% accuracy - and they’re doing it 6 to 9 months faster than traditional methods. By 2027, the FDA wants 45% of label updates to come from real-world data, up from just 18% in 2022.

This isn’t just about better labels. It’s about saving lives. Between 2010 and 2020, 62% of serious drug reactions were first detected through postmarketing surveillance, not clinical trials. That’s why this section exists - not to scare you, but to give you the full picture.

Bottom Line: Don’t Skip It

Postmarketing experience sections aren’t fine print. They’re the hidden safety net. They’re where the real story of a drug’s risks emerges. If you’re a patient, ask your doctor: “What’s in the postmarketing section of this drug?” If you’re a clinician, spend three minutes reading it every time you prescribe something new. Don’t assume rarity means safety. Don’t ignore vague language. And never assume absence means no risk.

The FDA doesn’t add things to this section lightly. Every line is a warning from real people - sometimes hundreds of them - who took the drug and had a bad reaction. Your job isn’t to panic. It’s to pay attention. Because in drug safety, the most dangerous side effects aren’t the ones you know about. They’re the ones you don’t.

Are side effects listed in the postmarketing section less serious than those in clinical trials?

No. Side effects listed in the postmarketing section are not necessarily less serious. They’re often rarer or less common, but they can be life-threatening. For example, a reaction like liver failure or severe allergic reaction might only appear after thousands of people take the drug. The clinical trial section lists common side effects seen in controlled studies. The postmarketing section reveals the hidden dangers that only show up in the real world.

What does ‘isolated reports’ mean on a drug label?

‘Isolated reports’ means the FDA received a few case reports of a side effect, but there isn’t enough data to confirm how often it happens or if the drug definitely caused it. It doesn’t mean the reaction is harmless. It means the evidence is limited. In some cases, ‘isolated reports’ have later turned out to be early signs of a serious pattern - like fatal bleeding events that were initially dismissed as rare accidents.

Can a side effect be missing from the postmarketing section and still happen?

Yes. The FDA explicitly states that if a side effect isn’t listed in the postmarketing section, it doesn’t mean the drug can’t cause it. Many reactions go unreported, or take years to show up. The section only includes what’s been reported and reviewed - not every possible side effect. Always assume there’s more you don’t know.

Why do some drugs list the same side effect in both clinical and postmarketing sections?

Sometimes, a side effect is seen in clinical trials but becomes more common or more severe after the drug hits the market. In other cases, different data sources give conflicting frequency estimates. For example, a reaction might be listed as ‘common’ in trials but ‘uncommon’ in postmarketing reports because real-world use includes older patients or people on multiple medications. This inconsistency doesn’t mean the label is wrong - it means the drug’s risk profile changes outside the lab.

How often are drug labels updated based on postmarketing data?

Between 2007 and 2017, 38% of all drug label updates were due to new safety information from postmarketing experience. The FDA now requires manufacturers to update labels as soon as new, significant risks are confirmed. With new AI tools and real-world data systems, updates are happening faster than ever - and more of them are driven by actual patient outcomes, not just trial data.

This is the part where the pharmaceutical companies go ‘lol just kidding’ after they make billions. You think they care about your liver? Nah. They care about the next quarter’s earnings. That ‘isolated report’ of liver failure? That’s someone’s kid in Ohio who’s now on a transplant list. And the company’s stock? Still going up. 🤡

So let me get this straight - the FDA’s entire safety net is built on ‘we saw something weird once’ and hope someone else reports it too? And we call this ‘science’? 😂

lol imagine trusting a label written by lawyers who’ve never taken a pill in their life 😅

The language in Section 6.2 is intentionally vague because causation is hard to prove. That doesn’t make it less real.

It’s wild how we treat drug labels like sacred texts when they’re basically a patchwork of guesses, lawsuits, and delayed reports. We need better systems - not just better reading.

USA still thinks its FDA is the gold standard? Bro, India’s pharmacovigilance system catches more real-world reactions in a week than your system does in a year. We have 1.4 billion people taking meds with zero corporate interference. Your ‘isolated reports’? We call them ‘daily occurrences’.

they're using FAERS to track you. every time you take a pill, they log it. they know what you're on. they know when you stop. they know when you die. this isn't safety. this is surveillance. the fda is a front for the deep state. they're building a biometric database under the guise of 'adverse events'. watch the next update - they'll start requiring your dna with your rx.

It’s honestly so sad how little people understand medical language. I’ve had patients cry because they thought ‘rare side effect’ meant ‘impossible to happen.’ You can’t just skim the tiny print and expect to live. If you don’t read the whole thing, you’re gambling with your life. And honestly? That’s on you.

The postmarketing experience section is a vital tool for public health - not a loophole, not a joke. It represents the collective wisdom of millions of real-world experiences. We should be investing more in improving reporting systems, not mocking the language that makes them possible.

While the language may appear ambiguous, it reflects the scientific rigor required to distinguish correlation from causation. In India, we emphasize patient education alongside label comprehension - a model worth adopting globally.

bro the real joke is that we pay $500 for a pill and then get a novel as the fine print. like… why not just give us a meme instead?

they're lying. the side effects are in the data. they just hide them. they know what they're doing. they don't want you to know. the fda is owned by big pharma. they're killing people on purpose. it's all connected to the vaccines. they're testing new ones on us. you think this is about safety? no. it's about control.

Let’s not forget - this isn’t just about labels. It’s about cultural trust in institutions. In the U.S., we’ve been conditioned to trust the system until it fails us. In Japan, they delay drug approvals for years to gather more data. In Brazil, they have community pharmacists who walk patients through every line of the label. We don’t need better language - we need better systems, better education, and a willingness to stop treating medicine like a commodity. This isn’t just medical literacy. It’s civil literacy.

It is imperative that healthcare professionals and patients alike recognize the significance of postmarketing surveillance as an indispensable component of pharmacovigilance.

you think this is the first time they hid side effects? remember thalidomide? remember vioxx? they knew. they always knew. they just waited until the patent expired. now they're doing it again with the new diabetes drugs. you're not a patient - you're a test subject. and the doctors? they're paid to look away.