1

Dec,2025

1

Dec,2025

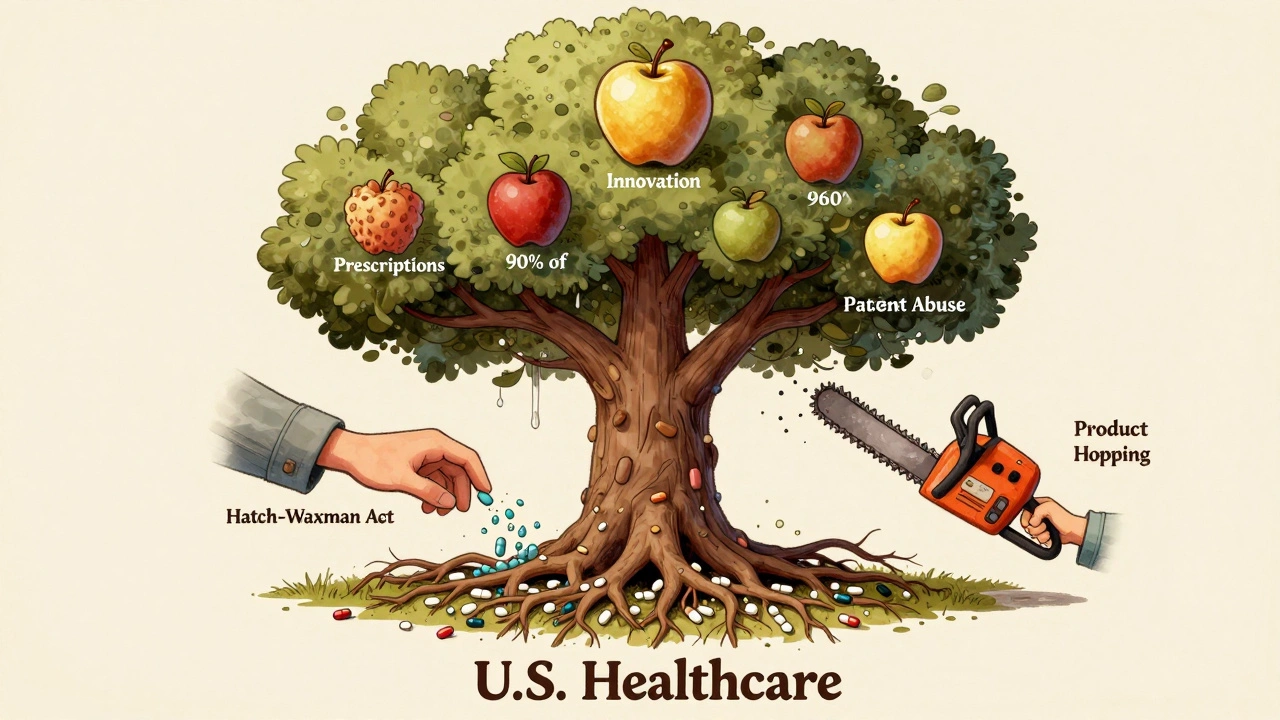

The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just change how generic drugs get approved-it rewrote the rules of the entire U.S. pharmaceutical market. Before 1984, getting a generic drug to market was slow, expensive, and often legally risky. The law that changed that? The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. Named after its sponsors, Congressman Henry Waxman and Senator Orrin Hatch, it was a hard-won compromise between big drug companies and generic manufacturers. And today, nearly every prescription you fill in the U.S. owes its existence to this law.

What the Hatch-Waxman Act Actually Did

Before 1984, generic drug makers had to run the same full safety and effectiveness tests as the original drug company-even though the drug was already proven safe. That meant spending hundreds of millions and waiting years just to get approval. The Hatch-Waxman Act cut that burden in half by creating the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA. Instead of redoing clinical trials, generic companies only needed to prove their version was bioequivalent-meaning it delivered the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug.

This wasn’t just a paperwork fix. It slashed development costs by about 75%. That’s why, by 2019, 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. were filled with generics-even though they made up only 24% of total drug spending. The savings? Over $1.18 trillion between 1991 and 2011, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

The Patent Safe Harbor: Why Generic Companies Could Start Early

Here’s where things got clever. Before Hatch-Waxman, testing a drug while its patent was still active was considered patent infringement. That meant generic companies couldn’t even begin development until the patent expired. The 1984 Supreme Court case Roche v. Bolar made this crystal clear.

Hatch-Waxman flipped that rule. It created a legal safe harbor under 35 U.S.C. §271(e)(1), allowing generic manufacturers to make, test, and study patented drugs during the patent term-only to gather data needed for FDA approval. That small change meant companies could start preparing years ahead. Instead of waiting for a patent to expire, they could file their ANDA up to five years before. That’s how generic drugs hit the market so fast after patent expiry.

Patent Term Restoration: The Trade-Off for Innovators

But the law didn’t just help generics. It also gave brand-name companies something back: the chance to get back some of the patent time they lost during FDA review. Developing a new drug takes 10-15 years. About half of that is spent waiting for FDA approval. That eats into the 20-year patent clock.

Hatch-Waxman let innovators apply to extend their patent by up to 14 years, but only for the time lost during regulatory review. In practice, the average extension granted was just 2.6 years. That sounds small, but for a blockbuster drug, it meant millions in extra revenue. Without this incentive, many companies say they wouldn’t have bothered investing in new drugs. The FDA approved 1,276 new molecular entities between 1984 and 2018. Experts estimate 30-40% fewer would have made it without Hatch-Waxman’s patent restoration.

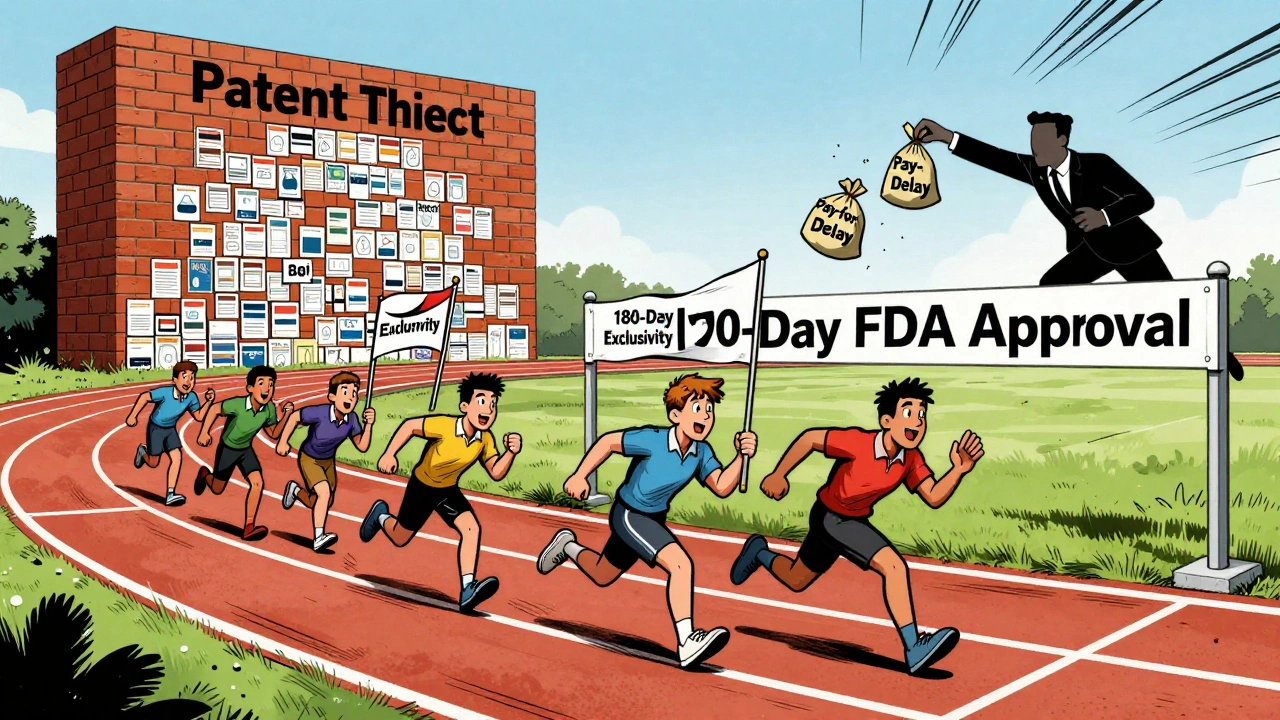

The Paragraph IV Gamble: How Generics Challenge Patents

One of the most powerful-and controversial-parts of the law is the Paragraph IV certification. When a generic company files an ANDA, it must check the FDA’s Orange Book, which lists all patents tied to the brand-name drug. If the generic believes a patent is invalid or won’t be infringed, it can file a Paragraph IV certification.

That triggers a 45-day window for the brand-name company to sue. If they do, FDA approval is automatically paused for 30 months. That’s a lot of time. But here’s the kicker: the first generic company to file a successful Paragraph IV gets 180 days of exclusive marketing rights. No other generic can enter during that time.

That created a mad dash. In the 1990s, companies would camp outside FDA offices to be the first to file. By 2003, the FDA changed the rules to let multiple companies share the exclusivity if they filed on the same day. But the stakes stayed high. A single 180-day window on a top-selling drug could mean hundreds of millions in profits.

The Dark Side: Patent Thickets and Pay-for-Delay

But the system didn’t stay fair for long. Brand-name companies started filing more patents-not on the drug itself, but on tiny changes: a new coating, a different dosage form, a slightly altered use. These are called “secondary patents.” In 1984, the average drug had 3.5 patents listed. By 2016, that number jumped to 2.7 per drug-wait, that’s not right. It jumped to 14 patents per drug, according to Professor Robin Feldman’s research.

This created “patent thickets”-a maze of overlapping patents that made it impossible for generics to enter without getting sued. Some drugs now face 50+ patents. Litigation can drag on for years. One generic company executive told Reddit users that for blockbuster drugs, the 180-day exclusivity window became meaningless because lawsuits stretched out for 7-10 years.

Then there’s “pay-for-delay.” Sometimes, instead of fighting in court, the brand-name company pays the generic maker to stay out of the market. Between 2005 and 2012, 10% of all generic challenges ended this way. The FTC called it anti-competitive. In 2023, the House passed the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act to ban these deals outright.

How the System Works Today

Today, the ANDA process is still complex. A typical application runs 30,000 to 50,000 pages. It takes 24-36 months to prepare. Even with the FDA’s Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), which added funding to speed up reviews, 43% of initial ANDAs still get rejected for major flaws.

But things are getting faster. Review times dropped from 36 months to 10 months on average. The FDA aims to cut that to 8 months by 2025. Meanwhile, the top 10 generic manufacturers now control 62% of the market-up from 38% in 2000. The industry has become more concentrated, and the cost to challenge a patent? $15-30 million per case.

The Big Picture: Generics Are the Backbone of U.S. Healthcare

Despite all the legal battles and loopholes, the Hatch-Waxman Act succeeded in its original goal: making drugs affordable without killing innovation. Today, generics account for 90% of prescriptions but only 18% of drug spending. They save the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $313 billion every year.

And the numbers don’t lie. In 1984, there were fewer than 10 generic approvals per year. In 2022, the FDA approved 771. There are now over 15,600 generic drug products on the market.

It’s not perfect. Patent abuse, pay-for-delay, and product hopping still happen. But without Hatch-Waxman, we wouldn’t have the access to affordable medicines we rely on today. The law didn’t just create a pathway for generics-it built a system that balances two powerful forces: the need for innovation and the need for access.

What’s Next?

Reform is coming. The 2022 CREATES Act stopped brand companies from blocking access to drug samples needed for testing. The 2023 Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act could ban pay-for-delay deals. The FDA is tightening rules on what patents can be listed in the Orange Book.

But the core of Hatch-Waxman remains. As a 2023 Deloitte survey found, 87% of pharmaceutical executives still believe the framework works-even if it needs updates. The goal isn’t to tear it down. It’s to fix the parts that got twisted.

It’s wild how one law could balance innovation and access so elegantly-until corporations started gaming it. The Hatch-Waxman Act was genius in theory, but like democracy, it only works if people respect the rules. Now we’ve got patent thickets thicker than a New York winter coat.

My grandfather took blood pressure medicine for 30 years-he couldn’t afford the brand, but generics kept him alive. This law didn’t just change markets, it saved lives. Thank you, Hatch and Waxman, wherever you are.

Generics are the unsung heroes of healthcare. No capes, no fanfare, just cheap pills that work. 🙌

Let me tell you something-India didn’t become the pharmacy of the world by playing nice. We made generics before Hatch-Waxman even existed. The U.S. just copied our playbook and slapped a patent on it. The real heroes? Indian chemists working 18-hour days in labs with no AC, making sure your $5 pill works just as well as the $500 one. And yes, I’m proud of that.

This whole system is a scam. Big Pharma owns the FDA, owns Congress, owns the courts. That 180-day exclusivity? It’s just a bribe wrapped in legal jargon. And don’t get me started on pay-for-delay-those are criminal deals disguised as contracts.

Technically, the phrase 'slashed development costs by about 75%' is statistically imprecise without a baseline. Also, '90% of prescriptions' doesn't equate to '90% of spending.' You're conflating volume with value.

Let’s be real-Hatch-Waxman didn’t just make generics affordable, it turned pharmaceuticals into a high-stakes poker game where the deck is stacked with patents, loopholes, and corporate greed. The FDA’s not a regulator-it’s a referee in a fight where one side has a flamethrower and the other has a rubber duck.

India’s generic industry is a joke. Their quality control is a mess. You think your $2 pill is safe? Good luck. I’ve seen reports-contaminated, underdosed, mislabeled. The U.S. system isn’t perfect but at least it has standards. You don’t get to play doctor with your country’s health.

Wait… did you know the FDA is secretly owned by Pfizer? They invented Hatch-Waxman to slow down generics so they could charge $100k for insulin. The 180-day exclusivity? That’s just a distraction. The real plan is to make you dependent on brand-name drugs forever. They’re already testing nanotech pills that track you. You’re being watched.

Look, the whole thing is a Shakespearean tragedy. The noble generic manufacturer, the cunning patent lawyer, the FDA caught in the middle like a confused king. And the people? Just the chorus, chanting 'We need this drug' while the curtain falls on another $200,000 cancer treatment. The law was meant to be a bridge-but now it’s a toll road with 17 booths and no cashiers.

Why are Americans so surprised? India has been making affordable medicine for decades. We didn’t need a U.S. law to figure out how to help our people. Your system is broken because you value patents more than people. We value survival. There’s no comparison.

It is, without hyperbole, one of the most consequential pieces of legislative architecture in modern American medical history. The delicate equilibrium between intellectual property rights and public health access-forged through bipartisan negotiation-remains a paradigmatic model of regulatory innovation, even as its implementation has been progressively eroded by corporate opportunism and litigation-driven obstructionism.

I appreciate the nuance here. The real tragedy isn’t the law-it’s that we stopped believing in compromise. Hatch and Waxman sat down, talked, and built something that worked. Today, we can’t even agree on whether water is wet. Maybe we need more lawmakers who care about patients, not profits.

Man, I just got my diabetes meds for $4 at Walmart. I don’t care if it’s branded or generic-I just care that I can afford to live. This law lets me breathe. Thanks to everyone who fought for this-even the ones who didn’t mean to.

Wow. Just… wow. You wrote a 2000-word essay on pharmaceutical policy and somehow missed the fact that the entire system is rigged. The FDA? Controlled by industry. The courts? A playground for lawyers. The 180-day window? A myth. The only thing that’s real is the money. And guess who’s getting it? Not you. Not me. Not the patient. The shareholders. Always the shareholders.