7

Feb,2026

7

Feb,2026

When your stomach hurts after eating, or you feel nauseous without any clear reason, it might not just be indigestion. It could be gastritis - inflammation of the stomach lining. This isn’t a one-time glitch; it’s a condition that can creep up slowly or hit hard all at once. And in most cases, it’s tied to a tiny, sneaky bacteria called Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori).

What Exactly Is Gastritis?

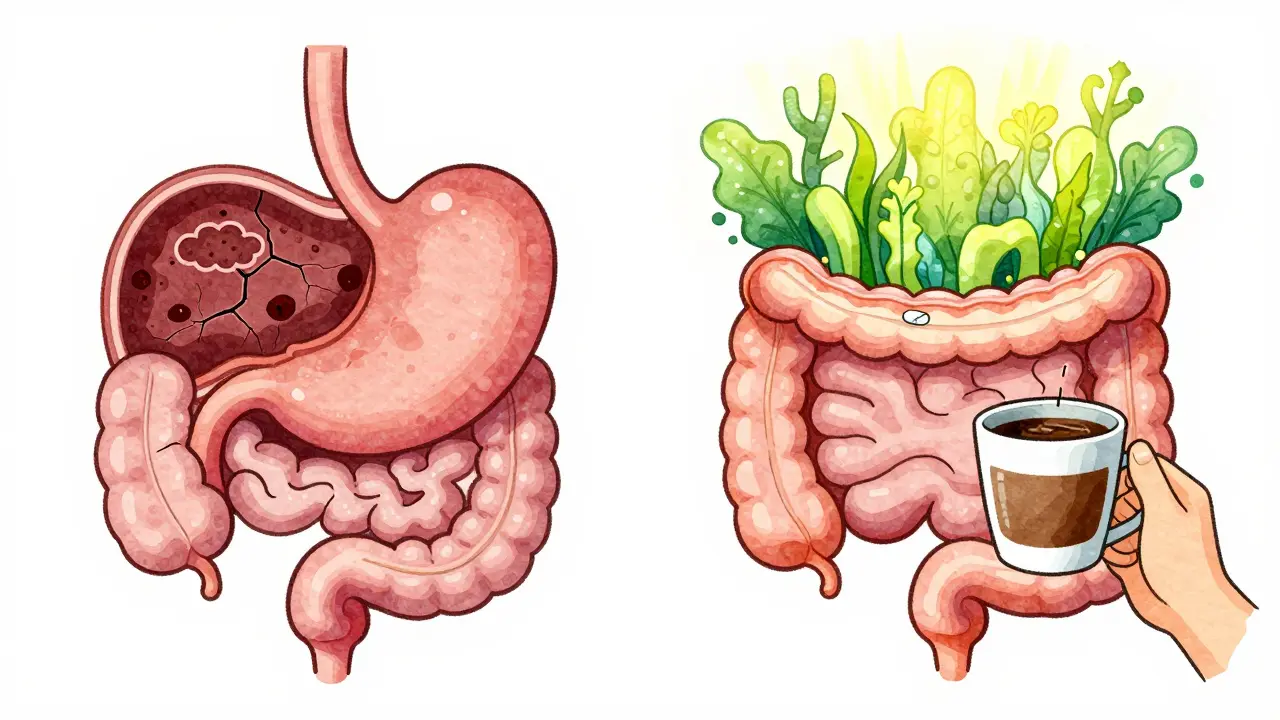

Your stomach lining, or mucosa, is designed to handle strong acids and enzymes that break down food. But when it gets inflamed, that protective barrier weakens. This leads to burning pain, bloating, nausea, and sometimes vomiting. Gastritis isn’t one single disease - it’s a spectrum. Some people have acute gastritis, where symptoms pop up suddenly after drinking too much alcohol, taking NSAIDs like ibuprofen, or severe stress. Others have chronic gastritis, which develops over months or years, often without obvious signs until complications arise.

Doctors split gastritis into two main types: erosive and nonerosive. Erosive means there are actual breaks or sores in the stomach lining - these can bleed, leading to black, tarry stools or even vomiting blood. Nonerosive gastritis doesn’t show visible damage, but the cells underneath are changing. In about 30% of people with long-term H. pylori infection, the stomach lining starts thinning out, losing its ability to produce acid. This is called atrophic gastritis and raises the risk of stomach cancer.

The H. pylori Connection

More than 70% of all chronic gastritis cases come from H. pylori. This spiral-shaped bacterium lives in the stomach, burrowing into the mucus layer where most other germs can’t survive. It’s not just hanging out - it’s causing damage. The bacteria release toxins that irritate the stomach wall and trick the immune system into responding, leading to long-term inflammation.

What’s wild is that most people with H. pylori never know they have it. Up to half of those infected show no symptoms at all. But for others, it’s the root cause of ulcers, chronic pain, and even gastric cancer. In fact, treating H. pylori cuts the risk of stomach cancer by about 50%. That’s why experts now treat it - even if you’re not feeling sick - if you live in a high-risk area or have a family history of gastric cancer.

Here’s the catch: H. pylori is super common. In developing countries, up to 80% of adults carry it. In Australia, about 20-30% of the population is infected. The older you are, the more likely you’ve been exposed. It spreads through contaminated food, water, or close contact - like sharing utensils or kissing someone who carries it.

Symptoms: More Than Just an Upset Stomach

Not everyone with gastritis feels the same way. Acute cases often bring sharp upper abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Chronic cases? Sometimes they’re silent. You might just feel full faster than usual, have bloating after small meals, or notice unexplained fatigue from low iron or B12 levels.

Red flags you shouldn’t ignore:

- Black, tarry stools - a sign of bleeding in the gut

- Vomiting blood or material that looks like coffee grounds

- Unexplained weight loss

- Persistent fatigue or shortness of breath - signs of anemia from slow bleeding

If you’re experiencing any of these, don’t wait. These aren’t normal digestive hiccups. They mean something more serious is happening.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Doctors don’t guess anymore. The gold standard is an endoscopy - a thin, flexible tube with a camera is passed down your throat to look at your stomach. Biopsies (tiny tissue samples) are taken to check for inflammation, H. pylori, or early signs of cancer.

But you don’t always need an endoscopy. Non-invasive tests are reliable:

- Urea breath test: You drink a special solution. If H. pylori is present, it breaks down the urea and releases carbon dioxide you exhale. This test is 95% accurate.

- Stool antigen test: Looks for H. pylori proteins in your poop.

- Blood test: Checks for antibodies, but can’t tell if the infection is current or past.

These tests are fast, painless, and widely available. No need to jump straight to an endoscopy unless you’re over 50, have a family history of stomach cancer, or are showing warning signs.

Treatment: Eradicating H. pylori

If H. pylori is the cause, treatment is straightforward - but not always easy. The standard is triple therapy: a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) like omeprazole or esomeprazole, plus two antibiotics - usually amoxicillin and clarithromycin - taken together for 10 to 14 days.

Success rates? Around 80-90% if you take every pill exactly as prescribed. But here’s the problem: antibiotic resistance is rising. In Australia and the U.S., clarithromycin resistance has jumped from 10% in 2000 to over 35% today. That means triple therapy fails more often than it used to.

That’s why doctors are switching tactics. In areas with high resistance, they use quadruple therapy: a PPI, bismuth (like Pepto-Bismol), metronidazole, and tetracycline. This works in 85-92% of cases. Another newer option is vonoprazan - a potassium-competitive acid blocker approved in 2022. It’s stronger at suppressing acid than PPIs and has shown 90%+ eradication rates in trials, even after failed treatments.

Side effects? Common ones include metallic taste, diarrhea, nausea, and stomach cramps. About 60% of patients report discomfort during treatment. But it’s temporary. The key is finishing the full course - even if you feel better after a few days. Stopping early invites resistant strains to survive.

What About Other Causes?

H. pylori isn’t the only culprit. NSAIDs like ibuprofen, naproxen, or aspirin can irritate the stomach lining, especially with long-term use. Alcohol, smoking, and severe stress (like after major surgery or burns) also trigger acute gastritis.

If NSAIDs are the problem, the fix is simple: stop or switch to a safer painkiller like acetaminophen. Add a PPI to protect your stomach while healing. For alcohol-related cases, cutting back or quitting can cut symptoms by 60% in just two weeks.

There’s also autoimmune gastritis - a rare form where your immune system attacks the stomach cells that make acid and intrinsic factor (needed for B12 absorption). This affects less than 1% of people but is more common in those with thyroid disease or type 1 diabetes. Treatment? Lifelong B12 injections.

Lifestyle Fixes That Actually Help

Treatment isn’t just pills. What you do outside the doctor’s office matters:

- Avoid NSAIDs: Use them sparingly. If you must take them, pair them with a PPI.

- Quit smoking: Smoking delays healing and increases cancer risk. Quitting improves healing by 35%.

- Limit alcohol: More than 30g/day (about 2 standard drinks) doubles your risk. Cut back or stop.

- Eat smaller meals: Large meals stretch the stomach, increasing pressure and discomfort.

- Avoid trigger foods: Spicy, acidic, or fried foods don’t cause gastritis but can make symptoms worse.

There’s no magic diet for gastritis. But many people find relief by eating more whole foods, less processed stuff, and avoiding eating right before bed.

What Happens After Treatment?

After finishing your antibiotics, you’re not done. You need confirmation that H. pylori is gone. That means a urea breath test or stool test 4 weeks after treatment ends. Why wait? Because the test can give false positives if done too soon - leftover bacteria or fragments can still show up.

If treatment fails? Don’t panic. Your doctor will try a different combo - maybe with different antibiotics or add vonoprazan. Some patients need two or three tries before it sticks.

Long-term PPI use? Many people stay on them for months or years. But beware: stopping suddenly can cause rebound acid production. That’s when your stomach overcompensates and makes even more acid than before. If you want to quit, do it slowly under medical supervision.

Why This Matters Now

Gastritis affects half a billion people worldwide. In Australia, the number of cases has been rising slowly, especially in older adults. But the real story is H. pylori’s role in cancer prevention. Treating it isn’t just about relieving pain - it’s about preventing death.

Experts predict that by 2030, better screening and tailored treatments could reduce H. pylori-related complications by 20%. But without action on antibiotic resistance, we risk seeing a comeback of ulcers and stomach cancer.

The message is clear: if you have chronic stomach issues, get tested. If you’re diagnosed with H. pylori, treat it fully. And if you’ve been on PPIs for years, talk to your doctor about whether you still need them.

Can gastritis go away on its own?

Acute gastritis caused by short-term triggers like alcohol or NSAIDs can resolve on its own once the irritant is removed. But chronic gastritis - especially from H. pylori - won’t disappear without treatment. Left untreated, it can lead to ulcers, bleeding, or even stomach cancer. Don’t assume it’ll fix itself.

Is H. pylori contagious?

Yes. H. pylori spreads through contaminated food, water, or close contact - like sharing utensils, kissing, or poor hygiene. It’s more common in crowded living conditions or areas with limited clean water. Most infections happen in childhood. Once you’re an adult, you’re less likely to catch it, but not impossible.

Can I test for H. pylori at home?

There are stool antigen test kits available for home use, but they’re not as reliable as lab tests. Blood tests can’t confirm active infection. The most accurate method - the urea breath test - requires a clinic visit. If you suspect H. pylori, see a doctor. Don’t rely on home tests alone.

Why do some people still have symptoms after treatment?

If H. pylori was the cause and it’s successfully eradicated, symptoms should improve. If they don’t, other issues could be at play - like functional dyspepsia, acid reflux, or another GI condition. Rebound acid from stopping PPIs can also mimic gastritis. Always follow up with your doctor if symptoms persist after treatment.

Are natural remedies like honey or probiotics effective?

Some studies suggest probiotics (like Lactobacillus) may reduce side effects from antibiotics and slightly improve eradication rates. Honey has antibacterial properties, but there’s no solid evidence it cures H. pylori. Don’t replace medical treatment with natural remedies. They might help as support, but not as a cure.

Okay so let me get this straight - H. pylori is the BOSS of stomach drama?? Like it’s just chillin’ in your gut like it owns the place?? I got tested last year after my stomach felt like a warzone for 3 months and turns out I had it. Doc gave me the triple therapy - omeprazole, amoxicillin, clarithromycin - and I swear I took every pill like my life depended on it. But guess what? I still felt like crap for 2 more months. Turns out my gut was just PISSED OFF from years of coffee, spicy food, and stress. So yeah, maybe the bacteria was the spark, but the whole damn house was on fire already. #GastritisIsNotJustABug

I just want to say thank you for writing this - seriously. I’ve been dealing with bloating and fatigue for years, and no one ever connected it to H. pylori. I finally got tested last month after reading your post, and it came back positive. I’m on treatment now, and even though the side effects are brutal (metallic taste?? Really??), I feel like I’m finally doing something right. You’re right - this isn’t just ‘indigestion.’ It’s a silent thief stealing your energy, your appetite, your peace. Thank you for giving me the nudge I needed. 💙

This is such a clear, well-written breakdown! I’ve been on PPIs for 5 years and never realized I could be at risk for rebound acid. I’m scheduling a consult next week to see if I can wean off. Also, I had no idea H. pylori was linked to cancer risk - that’s wild. I’m telling my whole family to get tested. My dad’s had ‘stomach issues’ since the 80s - maybe this is why. Thanks for the clarity and the urgency. 🙌

Wait… so you’re telling me the government and Big Pharma are hiding the TRUTH about H. pylori?? Like… why is this not on the news?? I’ve been reading about this for years - it’s not just about antibiotics… it’s about the microbiome, the gut-brain axis, the glyphosate in our food, the EMFs from our phones… I swear, if you stop all processed food and start taking colloidal silver and probiotics, your body can heal itself. I did it. My stomach’s been perfect for 3 years. No pills. No doctors. Just pure alkaline living. 😌✨

Look, I’ve had gastritis since I was 19. I was a college kid, drank too much, ate greasy pizza every night, smoked a pack a day - classic. Then I got diagnosed with H. pylori at 27. Triple therapy failed. Quadruple therapy failed. I was ready to give up. Then my GI doc said, ‘Try vonoprazan.’ I was like, ‘What? That’s not even a word!’ But guess what? It worked. Like, 100%. No more burning. No more nausea. I’ve been off meds for 18 months. I’m not saying it’s magic - I still avoid spicy food, I don’t drink anymore, I sleep 8 hours - but vonoprazan? It’s the real MVP. If you’ve tried everything else and still suffer - ask your doctor. It’s not a miracle, but it’s a game-changer. 🤯

Y’all are overcomplicating this. Just stop eating carbs. No sugar. No bread. No coffee. And boom - your stomach feels better. H. pylori? Probably just a symptom of sugar overload. I’ve seen it. I’ve lived it. I’m 32, no meds, no tests. Just keto. And I’m fine. Why do people need pills when the answer is in the fridge??

So if I get the urea breath test and it’s negative, does that mean I’m definitely cured? Or can it still be hiding? I did the treatment 6 weeks ago, got tested, and it said negative. But I still get weird bloating sometimes. Is that normal? Or should I go back? Just wanna know if I’m safe or if I’m just fooling myself.

OMG I JUST GOT MY RESULTS BACK AND IT’S NEGATIVE!!! 🎉 After 3 years of feeling like a ghost of myself - tired, bloated, always full after eating one slice of pizza - I did the treatment. It sucked. I had diarrhea for 10 days. But now?? I ate a burrito last night and didn’t regret it. I’m crying. Thank you for this post. You saved my life. 🤗💖

My mom had stomach cancer. She never had symptoms. Just… one day, she was gone. I’m getting tested tomorrow. I’ve been ignoring my bloating for 2 years. I think I’m done ignoring.