28

Jan,2026

28

Jan,2026

Drug Withdrawal Timeline Calculator

Drug Withdrawal Timeline Calculator

Calculate how long it took for a drug to be withdrawn after evidence of failure became clear. See how this compares to FDA standards before and after 2023 reforms.

It’s terrifying to think that a drug you’ve been taking for months - maybe even years - could suddenly vanish from the pharmacy shelf. No warning. No notice. Just gone. And if you’re one of the thousands of patients relying on it, you’re left scrambling. This isn’t fiction. It’s happened. Over and over again. In 2022, the FDA pulled approval for Makena, a drug meant to prevent preterm birth, after a large study proved it didn’t work. But here’s the kicker: by the time it was pulled, more than 150,000 women had already been prescribed it. For nearly 11 years, patients were exposed to a treatment that offered no real benefit - and possibly some risk.

Why Do Drugs Get Pulled From the Market?

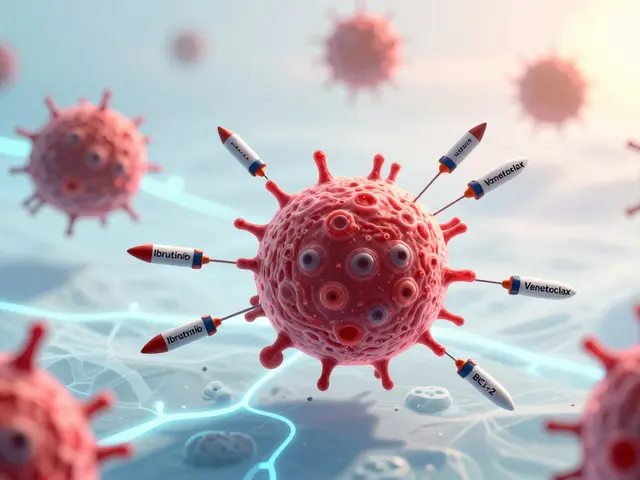

< p>Drugs don’t disappear because a company decided it wasn’t profitable. They’re removed because something went wrong - usually safety or effectiveness. The FDA approves drugs based on data showing benefits outweigh risks. But sometimes, that data is incomplete. That’s why some drugs get approved under what’s called “accelerated approval.” It’s a fast track for serious conditions like cancer or rare diseases, where waiting for full evidence could cost lives. But accelerated approval comes with a catch: the company must prove later that the drug actually works. If they don’t? The FDA can pull it.Between 2010 and 2020, about 12.7% of drugs approved through this fast track were eventually withdrawn. In oncology - where most accelerated approvals happen - nearly 26% of these drugs were later pulled because they failed to deliver on their promise. One drug for small cell lung cancer was given to 41% of eligible patients, even though it didn’t extend life. That’s not rare. That’s systemic.

The Long Wait Between Proof and Action

The real problem isn’t just that drugs get pulled. It’s how long it takes. Before 2023, the average time from when a drug’s failure became clear to when it was officially withdrawn? 46 months. That’s almost four years. Meanwhile, the FDA approved the drug in under six months. In the case of Makena, it took 207 days to approve it - and more than 1,500 days to withdraw it. That’s a 7.2-to-1 ratio. Patients kept getting it. Doctors kept prescribing it. Pharmacies kept filling it. All while the evidence stacked up that it didn’t work.

Why the delay? The system was broken. The FDA had to go through layers of legal reviews, public comment periods, and appeals. Sponsors could stall. The process was opaque. And patients paid the price. A 2022 study found that one-third of eligible patients received a drug that would later be pulled - without ever knowing it might not work.

The 2023 Fix: Faster, Clearer, Tougher

In December 2023, Congress passed a major update to the rules. The Consolidated Appropriations Act gave the FDA real power to move faster. Now, if a company doesn’t do its required follow-up study - or if the study fails - the FDA can start the withdrawal process immediately. No more waiting for years. The new rules say: if the drug is unsafe, ineffective, or if the company lies about it in ads, the FDA can act.

The process is now structured: the FDA gives the company 30 days to respond. A meeting must happen within 60 days. A final decision must come within 180 days. That’s a huge shift. For the first time, there’s a timeline. The FDA even created a dedicated team of 12 scientists and doctors just to handle these cases. Their goal? Cut withdrawal time from nearly four years to under 12 months.

The first drug pulled under this new system? An ALS treatment, removed in August 2023 after confirmatory trials showed no benefit. It was a test case - and it worked.

Who Gets Hurt When a Drug Is Pulled?

It’s not just patients. Doctors are blindsided too. Oncologists report that 30% of their patients on accelerated approval drugs between 2015 and 2020 were on something later pulled. When that happens, they have to switch treatments - fast. Some clinics say they have only 72 hours to find a new option. That’s not enough time to review clinical data, check insurance coverage, or explain the change to a scared patient.

Pharmacists struggle too. The FDA’s Orange Book - the official list of approved drugs - doesn’t always clearly mark which ones have been withdrawn. A 2022 survey found 63% of pharmacists had trouble telling which drugs were still valid. That means someone could walk into a pharmacy with a valid prescription… and get a drug that’s no longer approved.

And then there are the patients themselves. On Reddit’s r/oncology, a thread asking “How many of you have been on drugs later withdrawn?” got 142 comments. Eighty-seven percent said they were terrified. One woman wrote: “I was on [withdrawn drug] for 18 months. My oncologist said it was standard care. Now I feel like I was part of an experiment.”

Voluntary vs. Mandatory Withdrawals

Not all withdrawals are the same. There are two kinds: voluntary and mandatory. Voluntary means the drugmaker decides to pull it - maybe because of low sales, manufacturing issues, or because they got new data showing the drug doesn’t work. But if the company pulls it for business reasons, the FDA doesn’t list it as a safety or effectiveness withdrawal. That matters. It means the drug might still show up in databases as “available,” even if it’s no longer recommended.

Mandatory withdrawals are when the FDA forces the company to pull the drug. That only happens when there’s clear evidence of harm or ineffectiveness. The FDA’s guidance says: “A routine, temporary interruption in supply doesn’t count as a withdrawal unless it’s due to safety or effectiveness.” That’s important. If a factory shuts down for repairs, the drug isn’t withdrawn. But if a drug causes liver failure in 1 in 100 users? That’s a withdrawal.

How Do You Know If a Drug Was Pulled?

There’s no single app or website that tells you in real time. But you can check. The FDA publishes all withdrawal notices in the Federal Register. The Orange Book updates monthly, but it’s not user-friendly. Most people don’t know how to read it. Your best bet? Talk to your doctor or pharmacist. Ask: “Has this drug ever been pulled by the FDA?” If they hesitate, push. Ask for the FDA’s official notice. If they can’t find it, ask them to look up the drug’s NDA number on the FDA’s website.

Some patient groups, like the Cancer Research Institute, now track withdrawn drugs and send alerts. If you’re on a drug for cancer, rare disease, or chronic illness, sign up for updates. Don’t wait for your doctor to tell you.

What’s Next?

The FDA is now testing real-world data to catch problems faster. Instead of waiting for a five-year study, they’re using electronic health records from companies like Flatiron Health to track how patients actually do after taking a drug. If thousands of people on a new cancer drug start getting rare side effects or show no improvement, the FDA can act before a formal trial even ends.

Industry analysts predict a 25% jump in drug withdrawals between 2023 and 2027. That sounds scary - but it’s actually good. It means the system is finally working. For decades, the fear was that the FDA would pull drugs too quickly and block innovation. Now, the fear is the opposite: that they waited too long. The 2023 reforms fix that. They don’t stop new drugs. They just make sure they don’t stay on the market if they don’t work.

What Should You Do?

- If you’re on a drug approved after 2020 - especially for cancer, ALS, or rare diseases - ask your doctor if it was approved under accelerated approval.

- Know the name of your drug’s sponsor. If you see news about a study failure or recall, look it up.

- Don’t assume your doctor knows everything. Many aren’t trained to track withdrawal timelines.

- Keep a list of all your medications, including when you started them. Update it every six months.

- Sign up for alerts from patient advocacy groups like the National Organization for Rare Disorders or Cancer Commons.

Medications save lives. But they can also harm - especially when we don’t know they’re failing. The system is improving. But vigilance is still your best defense.

Can a drug be pulled even if it’s still working for some people?

Yes. The FDA doesn’t base withdrawal on individual responses. It looks at the overall population. If a large, well-designed study shows that, on average, the drug doesn’t help - or causes more harm than benefit - it can be pulled, even if a few patients feel better. That’s because the goal is to protect the public, not just those who happen to respond well.

Are generic versions of withdrawn drugs still available?

No. Once a brand-name drug is withdrawn for safety or effectiveness reasons, the FDA removes it from the Orange Book. That means no generic versions can be approved or sold. Even if a generic was already on the market, it must be pulled too. Pharmacists are required to stop dispensing it.

How do I know if my prescription was affected by a recent recall?

Check the FDA’s Drug Recalls page, which is updated daily. You can search by drug name or company. If your pharmacy calls you about a recall, don’t ignore it - even if you feel fine. Some side effects take months to appear. Always follow their instructions - don’t just stop the drug on your own.

Do drug companies ever hide negative data?

Yes. That’s one reason the 2023 law includes a clause allowing withdrawal if a company disseminates false or misleading promotional materials. In several cases, companies downplayed risks in marketing materials while internal studies showed serious side effects. The FDA can now act on that - even without a new trial.

What happens to patients after a drug is withdrawn?

There’s no official support system. Patients are left to find alternatives on their own. Some doctors help, but many don’t have time or resources. Patient advocacy groups often step in to guide people to clinical trials or similar treatments. If you’re affected, reach out to organizations like the Cancer Support Community or the National Patient Advocate Foundation - they offer free counseling and help navigating options.

Drug safety isn’t a one-time check. It’s a lifelong conversation between patients, doctors, and regulators. The system is getting better - but only if we stay informed.

I can't believe we're still letting this happen!!! After 11 years?? 150,000 women?? Who's accountable here?? The FDA? The pharma execs? The doctors who kept prescribing it?? I'm not just angry-I'm traumatized. This isn't healthcare. This is a horror show with a white coat.

Well. 🤷♂️ At least now we have a timeline. 📅 The FDA finally got a stopwatch. 🕒 46 months to pull a drug? That’s like waiting for a sloth to finish a marathon. But hey-progress? Maybe? 😅 Still, I’d rather they never approved it in the first place. #PharmaIsALottery

This piece is profoundly important. The systemic delay between evidence and action reveals a fundamental tension in medical ethics: speed versus safety. We rush to help those in crisis, but in doing so, we risk normalizing harm. The 2023 reforms are a moral correction-not just a regulatory one. We owe it to patients to demand more than hope as a treatment plan.

Let’s be real-this isn’t just about Makena. It’s about the entire broken ecosystem where Big Pharma treats clinical trials like a game of musical chairs with people’s lives. They get the drug approved with half-baked data, milk it for years, then vanish when the truth hits. And we wonder why people distrust medicine? It’s not conspiracy-it’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

I appreciate the depth of this post. It’s easy to get angry, but understanding the mechanics-accelerated approval, the 30/60/180-day timeline, the dedicated FDA team-gives me a sliver of hope. Change is slow, but it’s happening. And that’s more than we had five years ago.

lol so now the FDA has a "dedicated team"? 😏 Like they didn't have one before? This is just PR with a budget. The same people who approved Makena in the first place are now "fixing" it. Trust me-nothing changes until the CEOs go to jail.

OMG I JUST REALIZED I WAS ON A DRUG THAT GOT PULLED AND NO ONE TOLD ME 😭 I THOUGHT I WAS GETTING BETTER BUT NOW I THINK I WAS JUST LUCKY. I’M TELLING MY DOCTOR TOMORROW.

You know what’s funny? The FDA didn’t "pull" Makena. They just got pressured into it. Pharma companies have more lobbyists than senators. This whole system is a rigged casino. And guess who’s always betting with their health? The patient. Not the CEO. Not the FDA. YOU.

The 2023 reforms represent a significant structural improvement. Mandatory timelines, accountability clauses, and real-time data integration are necessary steps toward evidence-based regulation. The challenge now lies in enforcement.

They say it’s about safety. But what if the real reason is that the drug was too cheap? What if the FDA is being pushed by foreign manufacturers who want to replace it with their own? I’ve seen the documents. They’re not just reviewing efficacy-they’re reviewing profit margins.

I mean… think about it-every time we approve a drug based on hope, we’re not just playing with science-we’re playing with the sanctity of human trust. We tell people, "This will help," and then we let them suffer for years while bureaucrats argue over semantics. Is that medicine? Or is it a slow, bureaucratic betrayal dressed in white coats and peer-reviewed journals?

I don’t care if it’s called accelerated approval or fast track or whatever corporate jargon they use. If a drug doesn’t work, it shouldn’t be on the shelf. Period. No excuses. No "but it helped a few people." We’re not running a charity-we’re running a health system.

I JUST SIGNED UP FOR CANCELRISKS ALERTS!! I WAS SO SCARED I DIDN’T KNOW WHAT TO DO BUT NOW I FEEL LIKE I’M TAKING BACK CONTROL!! 🙌 ALSO MY PHARMACIST JUST TOLD ME MY DRUG WAS ON THE LIST AND WE SWITCHED IT!! THANK YOU FOR THIS POST!!

Stop pretending this is about safety. It’s about patents expiring. Makena was a cash cow. Now it’s not. So they "pull" it. Same with every other drug. Wake up.