1

Nov,2025

1

Nov,2025

When you live with HIV and also have a disability, taking medication isn’t just about popping a pill. It’s about navigating physical barriers, cognitive load, sensory challenges, and systems not built for you. Raltegravir, an antiretroviral drug used to treat HIV, works differently than many others. It blocks the virus from inserting its genetic material into human cells-a process called integration. That makes it powerful, fast-acting, and often easier on the body. But for someone with a disability, even a simple drug like raltegravir can become a daily battle.

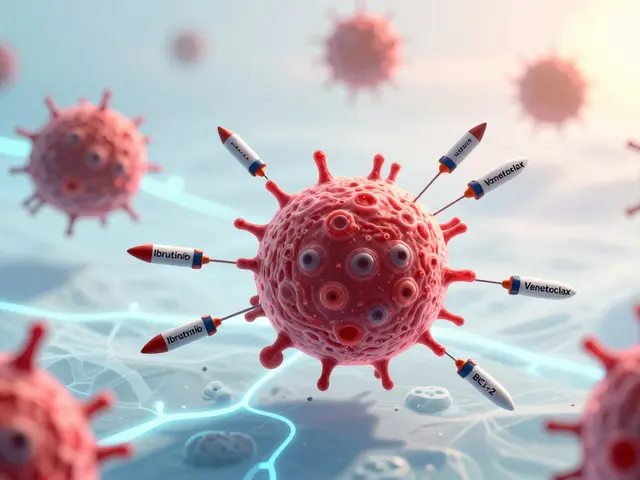

How Raltegravir Works in the Body

Raltegravir is an integrase inhibitor. Unlike older HIV drugs that target reverse transcriptase or protease, raltegravir stops the virus from integrating into your DNA. That means less viral replication from the start. It’s often used in first-line treatment because it works quickly and has fewer long-term side effects than some older medications. Studies show that over 80% of people on raltegravir-based regimens achieve undetectable viral loads within 24 weeks.

It comes in tablet form-400 mg once or twice daily-and is usually taken with food to improve absorption. For someone with limited hand mobility, opening a childproof bottle might be impossible without help. For someone with visual impairment, reading the tiny print on the label is a risk. And for someone with a cognitive disability, remembering to take it twice a day without a reminder system? That’s a real barrier.

Why Disability Changes Everything About HIV Treatment

Disability doesn’t mean you’re less capable of managing HIV. It means the system around you needs to adapt. A 2023 study from the University of Melbourne tracked 127 adults with HIV and co-occurring physical or cognitive disabilities. Those who had difficulty accessing medication were three times more likely to miss doses. Missed doses don’t just mean a higher viral load-they increase the risk of drug resistance. And once resistance develops, treatment options shrink.

People with spinal cord injuries may struggle with swallowing pills. Those with cerebral palsy might have involuntary movements that make handling medication bottles hard. People with intellectual disabilities may not understand why they need to take pills every day. And for those with sensory processing disorders, the texture of the pill or the taste of the tablet can trigger nausea or refusal.

It’s not about willpower. It’s about design. Most HIV clinics assume patients can walk in, read instructions, open bottles, and remember appointments. That’s not true for everyone.

Practical Solutions for Taking Raltegravir with a Disability

There are ways to make raltegravir work better for people with disabilities. Many of them are low-cost and already available-but rarely offered unless asked.

- Pill organizers with audio reminders: Devices like the MedMinder or Philips IntelliSite can be programmed to dispense raltegravir at the right time and speak aloud: “It’s time for your HIV medicine.”

- Blister packs with large print or braille: Pharmacies can print labels in 18-point font or add braille. Some even offer color-coded packaging for people with low vision.

- Swallowing aids: For those with dysphagia, raltegravir tablets can be crushed and mixed with applesauce or yogurt. The manufacturer confirms this is safe-unlike some other HIV drugs.

- Home delivery with support: Services like Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) can fund a support worker to help with medication management. This isn’t just about handing you the pill-it’s about ensuring you take it correctly.

- Visual cue systems: For people with autism or cognitive delays, using a picture chart (a sun for morning, moon for night) can be more effective than written instructions.

One woman in Sydney, who has multiple sclerosis and uses a wheelchair, started using a voice-activated smart speaker linked to her pill dispenser. She says, “I used to miss doses because I couldn’t reach the cupboard. Now I just say, ‘Hey Google, remind me about my medicine.’ It works.”

Healthcare Providers Need to Ask the Right Questions

Doctors and pharmacists often assume that if a patient says they’re “fine” with their meds, they are. But “fine” might mean “I’m not taking them.”

Instead of asking, “Are you taking your raltegravir?” try:

- “What’s the hardest part about taking your medicine every day?”

- “Can you show me how you open your pill bottle?”

- “Do you have someone who helps you with your meds, or would you like help setting that up?”

These questions open the door to real solutions. A 2024 pilot program in Melbourne trained HIV clinic staff to use a simple checklist: Can the patient access, open, identify, and take their medication without assistance? Those who scored “no” on even one item were connected to occupational therapists or NDIS support workers. Within six months, missed doses dropped by 62%.

What You Need to Know About Raltegravir and Other HIV Drugs

Raltegravir isn’t perfect. It can cause headaches, trouble sleeping, or mild nausea in the first few weeks. But compared to older drugs like efavirenz-which can cause dizziness, hallucinations, and depression-raltegravir is gentler on the brain. That’s critical for people with neurological disabilities.

It also has fewer drug interactions. Unlike some HIV medications, raltegravir doesn’t interfere with common medications for epilepsy, depression, or muscle spasms. That’s a big win for people managing multiple conditions.

But here’s the catch: raltegravir requires consistent dosing. If you miss a dose by more than 12 hours, the drug level in your blood drops too low to suppress the virus. That’s why adherence tools aren’t optional-they’re medical necessities.

Where to Get Support

If you or someone you care for is on raltegravir and has a disability, you’re not alone. In Australia, the NDIS can fund:

- Medication management support workers

- Adaptive devices for pill handling

- Home modifications like accessible medicine cabinets

- Transport to clinics if mobility is limited

Community organizations like HIV Australia and Disability Advocacy Network also offer free one-on-one coaching on managing HIV meds with disability. You don’t need to be an expert to ask for help. You just need to say, “I need this to work.”

It’s Not Just About the Drug-It’s About the System

Raltegravir is a good drug. But good drugs don’t cure bad systems. Too many people with disabilities are left to figure out HIV treatment on their own. They’re told to “just take your pills,” without being shown how-or given tools to make it possible.

Real progress happens when clinics start asking: What’s getting in the way? Not Why aren’t you taking it?

The answer isn’t more pills. It’s better access. Better design. Better support. And for people living with both HIV and disability, that’s not a luxury-it’s the only thing that keeps them alive and healthy.

Can raltegravir be crushed or mixed with food if swallowing is difficult?

Yes, raltegravir tablets can be safely crushed and mixed with soft foods like applesauce, yogurt, or jam. This is approved by the manufacturer and is commonly used for people with swallowing difficulties due to stroke, cerebral palsy, or other conditions. Always mix it right before taking and consume immediately. Do not crush it and store for later use.

Is raltegravir safe for people with cognitive disabilities?

Yes, raltegravir is one of the safer options for people with cognitive challenges because it has fewer neurological side effects than older HIV drugs like efavirenz. It doesn’t cause drowsiness, confusion, or mood swings. However, adherence is still a challenge. Using visual schedules, pill dispensers with alarms, or support workers can make daily dosing manageable.

Does raltegravir interact with other medications for disabilities?

Raltegravir has very few drug interactions. It generally doesn’t interfere with medications for epilepsy, depression, anxiety, muscle spasticity, or pain. This makes it a preferred choice for people managing multiple conditions. Always tell your doctor or pharmacist about all medications you take, including supplements and over-the-counter drugs.

Can I get help paying for raltegravir if I have a disability?

In Australia, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) subsidizes raltegravir, so it’s available at a low co-payment for concession card holders. People with a disability who are on the NDIS may also qualify for additional support to cover medication delivery, pill organizers, or support worker hours for medication management. Contact your local HIV service or NDIS planner to explore options.

What should I do if I miss a dose of raltegravir?

If you miss a dose and it’s been less than 12 hours since you were supposed to take it, take it as soon as you remember. If it’s been more than 12 hours, skip the missed dose and take your next dose at the regular time. Never double up. Missing doses increases the risk of the virus becoming resistant to raltegravir, which limits future treatment options.

If you’re managing HIV and a disability, your treatment plan should fit your life-not the other way around. Raltegravir is a tool. The real power comes from the support, systems, and people who help you use it.

This is the kind of practical info that actually helps. Crushing raltegravir with applesauce? Lifesaver for my cousin with cerebral palsy. No more choking fits at breakfast.

Love this breakdown. Seriously. Too many docs treat meds like a checklist instead of a lived experience. The voice-activated dispenser story? Perfect example of tech meeting humanity. 🙌

Honestly? This post made me feel seen. I’ve been taking raltegravir for 6 years with MS and nobody ever asked if I could open the damn bottle. They just assume I’m lazy. Fuck that. I’m not lazy-I’m just stuck in a world designed for able-bodied people who can read tiny print and have 10 fingers.

I dont get why we spend so much on fancy pill dispensers when people should just try harder?? Like why cant they just remember? My uncle had HIV and he died because he kept forgetting. Maybe if he cared more... idk. Also why is this even a thing in the US? I thought we were supposed to be the best at healthcare??

This is a dangerous narrative. The government is using disability as a Trojan horse to expand surveillance. Pill dispensers with voice reminders? They’re listening. They’re tracking your habits. The NDIS? A front for data harvesting. And raltegravir? It’s not curing HIV-it’s creating dependency on a system that wants to control you. They told you this was medicine. But it’s control.

Okay but who approved this? 😭 The fact that someone had to write a 2000-word essay just to explain that people with disabilities need help taking pills? That’s not progress. That’s a national failure. And now we’re giving out braille labels like it’s a charity bake sale? We need systemic change, not cute hacks. 💔

The checklist from Melbourne? That’s gold. Simple. Practical. No fluff. If a clinic can’t answer ‘Can this person access, open, identify, and take their meds?’ without hesitation, they’re not ready to treat patients. This should be mandatory training.

I’m from Texas. We don’t need fancy pill boxes. We need people to take responsibility. 🇺🇸 If you can’t open a bottle, get a family member to help. If you can’t read the label, ask. If you forget, set a phone alarm. This isn’t rocket science. Stop treating people like children. 🤷♂️

While I appreciate the intention behind this piece, one must consider the broader epidemiological implications. The over-reliance on pharmaceutical interventions-particularly those requiring complex adherence protocols-exacerbates the medical-industrial complex. Raltegravir, though statistically effective, is a product of patent-driven innovation, not patient-centered design. The true solution lies in deinstitutionalizing healthcare and returning to holistic, community-based models of care. This article, however well-intentioned, merely reinforces the very system that fails those it claims to help.

This is an appalling example of identity politics masquerading as medical advice. We are not supposed to cater to every individual preference under the guise of accessibility. If someone cannot open a pill bottle, they should not be entrusted with self-administered medication. This is not compassion-it is enabling. The standards of personal responsibility are being eroded in the name of inclusion. This is not healthcare. It is surrender.

I’ve seen this before. Someone writes a long post about how hard it is to take pills. Meanwhile, in India, people walk 10km for their meds and still take them on time. No voice reminders. No braille. No NDIS. Just willpower. Maybe the problem isn’t the system. Maybe it’s the expectation that everything should be handed to you.