20

Nov,2025

20

Nov,2025

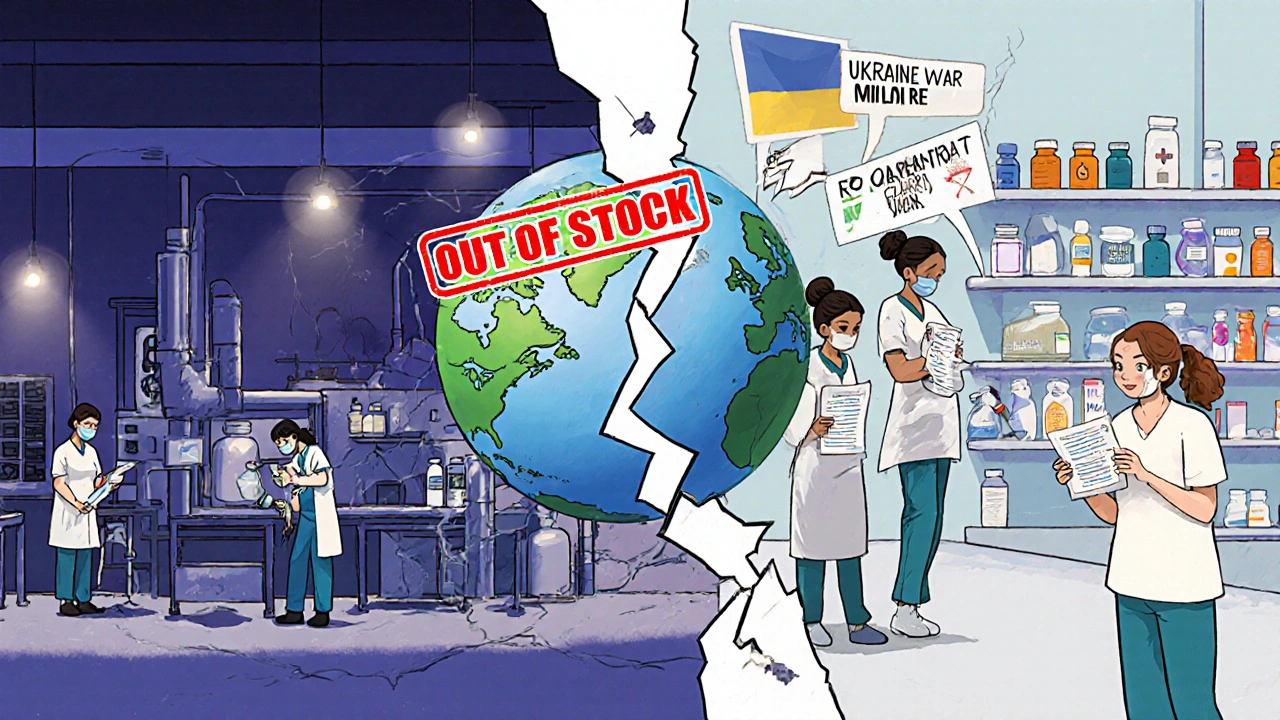

When medicines disappear and prices spike

It’s November 2025. You walk into your local pharmacy to refill your blood pressure medication. The pharmacist shakes their head. "We’re out. No shipments in until January." You ask about alternatives. They tell you one option costs 300% more. This isn’t a one-off. It’s happening across Australia, the U.S., and Europe. Medications, medical devices, even basic supplies like IV bags and syringes are vanishing. And when they’re available, the price tag is brutal.

This isn’t just bad luck. It’s the result of deep, interconnected economic forces: pricing pressure and shortages. These aren’t abstract terms. They’re real, daily realities for patients, doctors, and hospitals. And they’re driving up the cost of health care faster than wages or inflation can keep up.

Why do drugs suddenly disappear?

Shortages don’t happen because no one makes the drug. They happen because the system can’t keep up. Take the case of generic injectable antibiotics. In 2021, a single factory in India that produced 40% of the world’s supply shut down for regulatory issues. That one event triggered global shortages. Why? Because most countries rely on just one or two suppliers for these low-margin drugs. When one fails, there’s no backup.

Supply chains in health care are built for efficiency, not resilience. Companies cut costs by outsourcing production to low-wage countries, minimizing inventory, and relying on just-in-time delivery. That works fine until a storm hits - like the pandemic, war in Ukraine, or a port strike. Then everything freezes. The San Francisco Federal Reserve found that supply chain disruptions raised U.S. goods inflation by up to 1.5 percentage points during 2021-2022. For medicines, the impact was worse. A 2023 study showed that 72% of critical drug shortages were tied directly to foreign production delays.

Why do prices jump when supplies drop?

Basic economics says: less supply, higher price. But in health care, it’s messier. When a drug becomes scarce, manufacturers don’t always raise prices immediately. Sometimes they wait. But when they do, they know patients have no choice. A 2022 U.S. Government Accountability Office report found that when a single-source generic drug faced a shortage, its price increased by an average of 420% within six months.

It’s not just the drug makers. Distributors and pharmacies also adjust prices. With limited stock, they prioritize buyers who pay more - hospitals over clinics, private insurers over public programs. This creates a two-tier system: those who can afford it get the medicine. Those who can’t wait, or pay, go without.

Price controls make it worse. In the UK, the government capped how much pharmacies could charge for certain drugs. The result? Suppliers stopped delivering. Between August and December 2021, 27 small health care suppliers went bankrupt because they couldn’t cover costs. The same thing happened in Australia with insulin and asthma inhalers in 2023. When prices can’t rise to match scarcity, supply vanishes.

Who pays the biggest price?

It’s not the big hospital chains or insurance companies. It’s the patient.

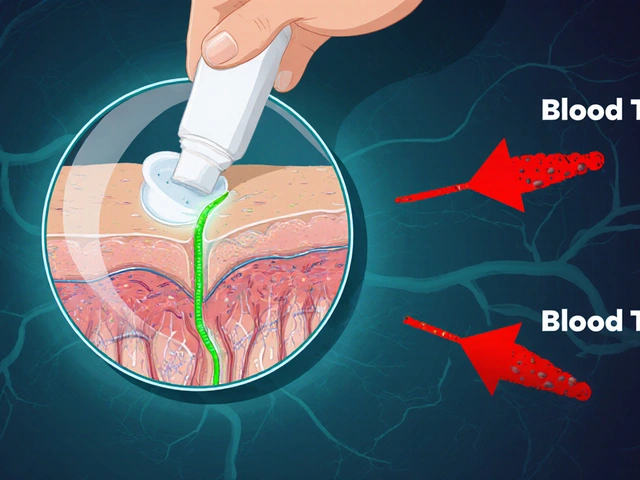

People with chronic conditions - diabetes, heart disease, epilepsy - are hit hardest. When their insulin, metformin, or seizure meds go out of stock, they don’t just miss a dose. They risk hospitalization. A 2023 study in The Lancet found that drug shortages in Australia led to a 17% increase in emergency visits for uncontrolled diabetes over a 12-month period.

Low-income patients are the most vulnerable. They can’t afford to switch to expensive alternatives. They can’t travel to another pharmacy. They can’t wait months for a shipment. In Melbourne, a 68-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis skipped her biologic injections for five months because her Medicare subsidy didn’t cover the new, higher price. Her joint damage worsened. She now needs surgery.

Even when the drug is available, the cost burden shifts. Insurers raise premiums. Employers cut benefits. Patients pay more out-of-pocket. The average Australian now spends 18% more on prescription drugs than they did in 2019 - and that’s before factoring in the hidden cost of missed work or delayed treatment.

Why aren’t more drugs being made locally?

It’s cheaper to make pills in India or China. Labor is cheaper. Regulations are looser. But that’s the problem. When 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients come from just two countries, you’re one geopolitical crisis away from chaos.

Some governments are trying to fix this. The U.S. passed the CHIPS and Science Act to boost domestic production. Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration now offers fast-track approval for local manufacturers of critical drugs. But building a new factory takes five years. And it costs hundreds of millions. No company will invest unless they’re guaranteed buyers - and that means government contracts.

Germany tried a different approach in 2021. They temporarily relaxed competition rules so that drug makers could share production capacity. The result? Pharmaceutical shortages dropped by 19% in six weeks. Australia could do the same. But political will is weak. It’s easier to blame “global supply chains” than to fund local solutions.

What’s being done - and what’s not

Some hospitals are stockpiling. They’re buying six months’ worth of insulin or antibiotics, even if it ties up cash. That helps - but it’s not sustainable. And it doesn’t help smaller clinics or pharmacies.

Others are switching to alternatives. But not all drugs have safe substitutes. For rare cancers or autoimmune diseases, there’s often only one effective treatment. When it’s gone, there’s no Plan B.

Technology offers hope. Digital supply chain tracking tools help predict shortages before they happen. One Australian hospital system reduced drug stockouts by 31% in 2024 by using AI to monitor global supplier data. But these tools are expensive. Only big institutions can afford them.

The real fix? More diversity. More local production. Better government coordination. And a shift away from the idea that health care should be treated like a commodity - where the cheapest bid wins, no matter the risk.

What patients can do

It’s not fair that patients have to become supply chain experts. But here’s what helps:

- Ask your pharmacist about alternatives - even if they’re more expensive. Sometimes a different brand or formulation is available.

- Keep a 30-day supply of essential meds. Don’t wait until you’re out.

- Join patient advocacy groups - they’re pushing for policy changes on drug access and pricing.

- Report shortages to your national health authority. The more reports, the more pressure to act.

One woman in Adelaide started a simple spreadsheet tracking which pharmacies had metformin in stock. She shared it with her diabetes support group. Within months, 200 people were using it. That’s not a policy change - but it saved lives.

The road ahead

Supply chain pressures have eased since 2022. Global shipping delays are down. Inflation is cooling. But the underlying problems haven’t gone away. Climate change is disrupting crop harvests for plant-based drugs. Geopolitical tensions are forcing companies to rethink where they make things. Labor shortages in manufacturing persist.

The International Monetary Fund predicts supply chain disruptions will stay 15-20% above pre-pandemic levels through 2025. That means more shortages. More price spikes. More people choosing between medicine and rent.

Health care isn’t just about doctors and hospitals. It’s about the invisible systems that deliver pills, syringes, and vaccines. When those systems break, people suffer. And the cost isn’t just financial - it’s measured in missed birthdays, delayed treatments, and lives cut short.

Fixing this won’t be easy. But ignoring it will cost far more.

Why are generic drugs so hard to find?

Generic drugs are low-margin products, so manufacturers often produce them in just one or two overseas factories to cut costs. If that factory shuts down - due to regulatory issues, natural disasters, or political unrest - there’s no backup. Unlike brand-name drugs, generics rarely have multiple suppliers. That makes them extremely vulnerable to disruption.

Can price controls solve drug shortages?

No - they usually make shortages worse. When governments cap how much pharmacies can charge, manufacturers and distributors lose money on low-margin drugs. They stop producing or shipping them. The UK saw 27 small health suppliers go bankrupt in late 2021 after enforcing price caps on essential medicines. Without room to raise prices when costs rise, supply disappears.

Why don’t we make more medicines locally?

Building a drug manufacturing plant costs hundreds of millions and takes 5+ years. Most companies prefer to outsource to cheaper countries like India and China. Without government subsidies, contracts, or guaranteed demand, local production isn’t profitable. Some countries are starting to change this - Australia now offers faster approvals for local drug makers - but progress is slow.

How do supply chain issues affect public health?

When essential drugs like insulin, antibiotics, or heart medications disappear, patients delay or skip treatment. This leads to more hospitalizations, complications, and deaths. A 2023 study in The Lancet linked drug shortages to a 17% spike in emergency visits for uncontrolled diabetes in Australia. The health cost is real - and far higher than the price of preventing shortages.

What’s the difference between a shortage and a price spike?

A shortage means the drug isn’t available at all - no stock. A price spike means it’s available, but at a much higher cost. Both are symptoms of the same problem: broken supply chains. But a price spike can be temporary if demand cools. A shortage often means production has stopped - and that takes months or years to fix.

The system is designed to optimize for profit, not people

It’s not broken-it’s working exactly as intended

When you treat medicine like a commodity, you get commodity outcomes

We’ve forgotten that health isn’t a market segment

It’s a human right

And yet we let supply chains dictate who lives and who doesn’t

This isn’t about India or China or tariffs

It’s about what kind of society we’ve chosen to build

We reward efficiency over resilience

Low cost over care

And then act surprised when people die because they couldn’t afford the next pill

Maybe the real shortage isn’t of drugs

But of moral courage

From an API-driven pharma supply chain perspective, the root cause is structural monopsony in API sourcing coupled with thin margin elasticity

When you have 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) concentrated in two jurisdictions with fragile regulatory alignment, you create a single point of failure in a high-velocity, low-margin value chain

Just-in-time inventory models, optimized for COGS reduction, are inherently brittle under black swan events-pandemic, geopolitical disruption, or even monsoon season in Gujarat

The solution isn’t just reshoring-it’s diversification of Tier-1 suppliers with buffer stock protocols and dynamic pricing algorithms that trigger pre-emptive procurement when lead times exceed 90 days

And yes, price caps without subsidy equivalence are fiscally suicidal

They induce supply withdrawal via negative arbitrage

It’s basic microeconomic equilibrium-when price is artificially constrained below marginal cost, output collapses

Hey everyone, I just wanted to say-this is so real

I work in a small clinic in rural Ohio, and we’ve had patients skip insulin for weeks because the price jumped from $30 to $180

One kid’s mom cried in my office because she had to choose between his meds and her rent

It’s not just statistics

It’s people

But here’s the good news-we started a local pharmacy partnership where we pool orders and get bulk discounts

And we’re teaching patients to track stock via a simple Google Sheet-just like that woman in Adelaide

Small wins matter

You don’t need a federal law to start helping someone today

Reach out to your pharmacist. Ask for alternatives. Share what you learn

We’re all in this together

So... we're just supposed to *feel bad* about capitalism now? 🤔

Maybe if people stopped demanding cheap drugs, factories wouldn't move overseas?

Also, why are we surprised? 🤷♂️

It's a free market, bro. If you want it bad enough, pay for it.

Also, I'm pretty sure this is just a woke narrative to justify higher taxes 😏

Also also-has anyone considered that maybe we're just too dependent on *other people's* factories? 🤔

Also also also-what if we just... didn't need meds? 🤔

Just saying. 🤷♂️

Oh, for crying out loud-this is why I HATE when we outsource EVERYTHING to countries that don’t care about our lives!

India? China? They’re not our friends-they’re our suppliers, and we treat them like gods while our own people suffer!

We let them control our medicine like it’s some kind of global monopoly game, and then we act shocked when the pieces disappear?

It’s not ‘global supply chains’-it’s betrayal!

Our own government let this happen because they were too busy kissing corporate butt to protect US citizens!

And now people are DYING because we’re too cheap to build our own factories?

Enough!

Build it here. Pay the cost. Protect the people.

Or keep pretending this is just ‘economics’-and watch your grandma die on a waiting list.

omg i had this happen last month with my asthma inhaler

my pharmacy had zero and the next one was 200 bucks

i was so scared i cried in the parking lot

but then i called my doc and they gave me a sample and told me to ask for the generic brand

and i started keeping a 30 day supply like they said

and joined my local patient group

it’s not perfect but it’s helping

you guys are not alone

and small things add up

even a spreadsheet can save a life 💪❤️

My sister died because they ran out of her chemo drug.

They told her it was a ‘supply issue.’

She waited three months.

She didn’t get a second chance.

Now I’m just waiting for the next one to disappear.

And I’m not crying anymore.

I’m angry.

And I’m not done.

Wait, so you’re telling me that if we just paid more for drugs, everything would be fine?

That’s it? That’s the solution?

What about the fact that drug companies are already making billions?

And why are we blaming the poor countries that make the pills when the real villains are the CEOs who moved production overseas to maximize quarterly profits?

And why does no one talk about how insurance companies refuse to cover alternatives even when they’re safer?

And why is the government letting this happen while giving tax breaks to pharma?

And why are we all pretending this is just ‘market forces’ and not deliberate, calculated greed?

And why is this post so long when the answer is simple: regulate them.

Not ‘spreadsheet’ solutions.

Not ‘patient advocacy.’

Regulate them.

Now.

And stop pretending this is complicated.