17

Nov,2025

17

Nov,2025

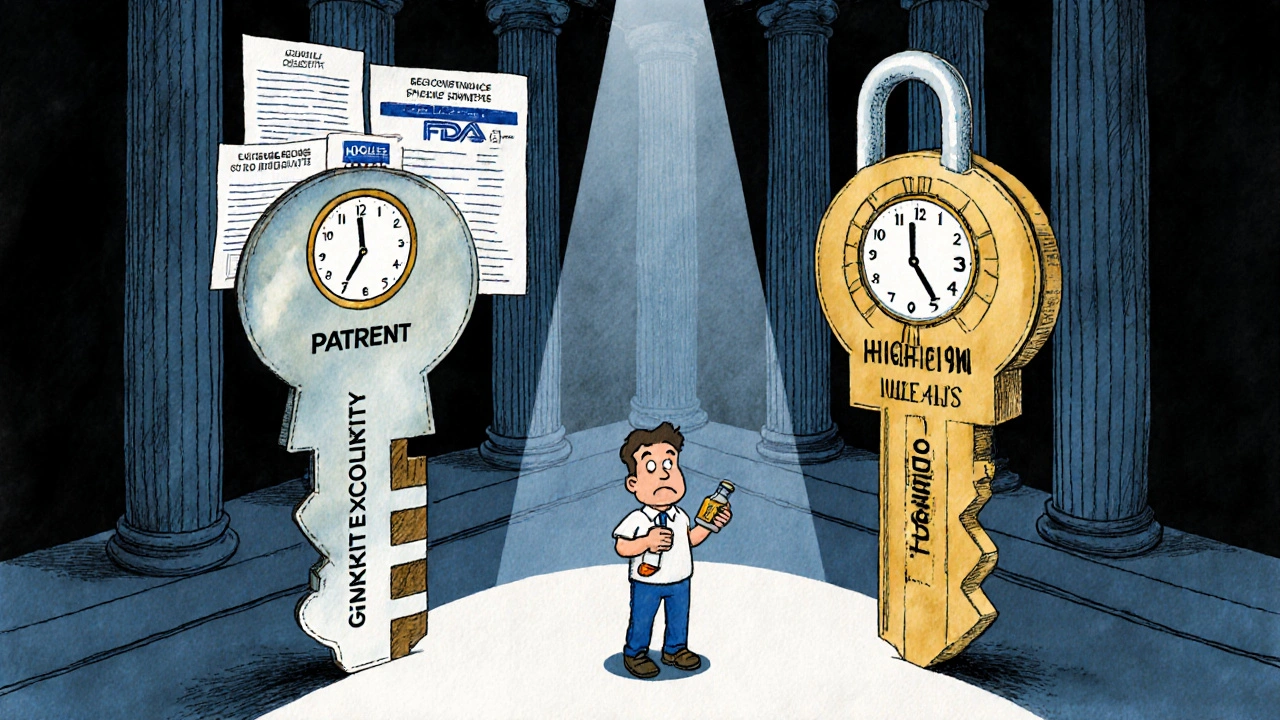

When a new drug hits the market, it doesn’t just come with a price tag-it comes with a legal shield. Two different kinds of protection keep generics off the shelves: patent exclusivity and market exclusivity. They sound similar, but they’re not the same. One comes from the patent office. The other comes from the FDA. And confusing them can cost billions-or leave patients paying way more than they should.

Patent Exclusivity: The Legal Right to Block Copies

Patents are about inventions. If you invent a new chemical compound, a new way to make it, or a new use for an old one, you can file for a patent. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) gives you the right to stop others from making, selling, or using that invention for 20 years from the date you filed the patent.

But here’s the catch: most drugs take 10 to 15 years to get approved by the FDA. That means by the time the drug actually hits shelves, you’ve already used up half your patent life. A drug filed for patent in 2010 might not be approved until 2020. That leaves only 10 years to make back the $2.3 billion it cost to develop.

That’s why companies get extensions. The law lets them ask for Patent Term Extension (PTE) to make up for time lost during FDA review. The max extension is 5 years-but the total time from FDA approval can’t go beyond 14 years. So even with extensions, real-world patent protection rarely lasts more than 12 years.

Patents can be tricky. The strongest one is a composition of matter patent-it covers the actual molecule. But many companies file secondary patents instead: for new formulations, dosages, or uses. These are easier to get and harder to challenge. In fact, 68% of patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book are secondary patents, not the core invention. That’s why some drugs have 10+ patents stacked on top of each other-called a "patent thicket." It’s not always about innovation. Sometimes it’s about delaying competition.

Market Exclusivity: The FDA’s Silent Gatekeeper

Market exclusivity has nothing to do with patents. It’s a separate rule created by Congress in the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. The FDA grants it automatically when a drug is approved-if the company meets the criteria. No filing. No lawsuit. Just approval, and the clock starts ticking.

There are different types:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity: 5 years. During this time, the FDA can’t even accept an application for a generic version. No one can copy the data you used to prove the drug works.

- Orphan drug exclusivity: 7 years. For drugs treating rare diseases (under 200,000 patients in the U.S.). Even if there’s no patent, no one else can get approved for the same use.

- Pediatric exclusivity: 6 months added to any existing patent or exclusivity period. Companies get this by doing extra studies on kids, even if the drug was never meant for children.

- Biologics exclusivity: 12 years. For complex drugs made from living cells-like Humira or Enbrel. This one is longer because biologics are harder to copy.

- 180-day exclusivity: Given to the first generic company that successfully challenges a patent. They get to be the only generic on the market for six months. That’s worth hundreds of millions in extra sales.

Here’s the kicker: market exclusivity can exist even when there’s no patent at all. In 2010, Mutual Pharmaceutical got 10 years of exclusivity for colchicine-a drug used since ancient Egypt. It had no patent. But because they submitted new clinical data to get it approved for a new use, the FDA gave them exclusivity. The price jumped from 10 cents a pill to nearly $5. That’s market exclusivity in action: legal monopoly, no invention required.

How They Work Together (or Don’t)

Think of patents and market exclusivity as two different keys to the same lock. You need both to keep generics out. But if you lose one key, the lock might still stay shut.

Here’s how it breaks down:

- 27.8% of branded drugs have both patent and market exclusivity.

- 38.4% have only patents-so generics can come in as soon as the patent expires, even if the drug is still under FDA review.

- 5.2% have only market exclusivity-no patent at all. But generics still can’t touch them for 5, 7, or 12 years.

- 28.6% have neither-these are older drugs that anyone can copy.

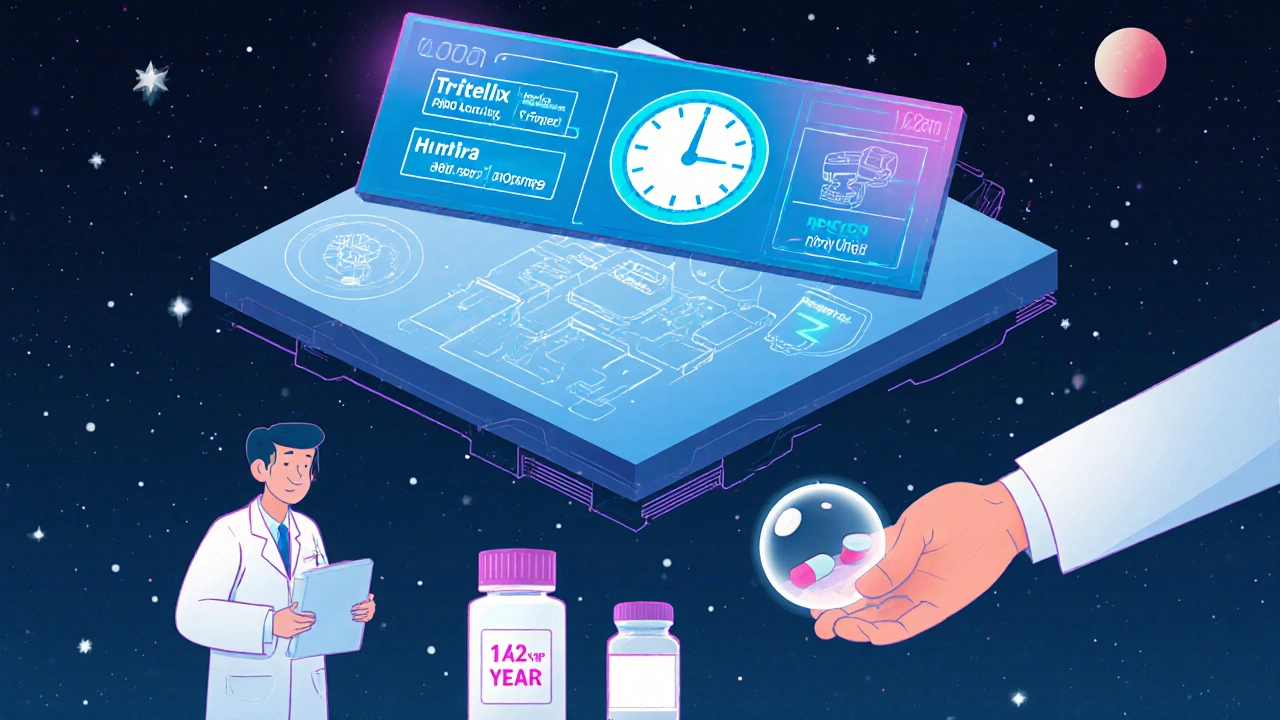

That’s why some drugs stay expensive long after their patent expires. Take Trintellix, an antidepressant. Its main patent expired in 2021. But because of 3 years of market exclusivity, generics couldn’t launch until 2024. Teva Pharmaceuticals lost an estimated $320 million waiting.

And here’s the real surprise: 78% of drugs with market exclusivity but no patent still had no generic competition during that time. The FDA’s exclusivity rule is often stronger than the patent.

Why This Matters for You

If you’re a patient, this system affects your out-of-pocket costs. If you’re a pharmacist, it affects what’s on the shelf. If you’re a small biotech company, it affects whether your drug survives.

Small companies often don’t realize that patents don’t guarantee market access. A 2022 survey by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization found that 43% of small firms mistakenly thought patent protection meant no generics could enter. They spent millions developing drugs, only to find out their exclusivity claim was incomplete-and generics slipped in early.

On the flip side, generic makers spend $8.3 million on average just to challenge a single patent. And if they win, they get 180 days of monopoly profits. That’s why some generics go after patents they know are weak-just to get that window.

Even the FDA makes mistakes. Between 2018 and 2022, 22% of drug companies didn’t claim all the exclusivity they were entitled to. On average, they left 1.3 years of protection on the table. That’s free money they didn’t even know they had.

What’s Changing Now?

The rules are shifting. In 2023, the FDA launched a public Exclusivity Dashboard so anyone can track when exclusivity periods end. It’s a game-changer for generics-they can plan their entry months in advance.

Also, the PREVAIL Act of 2023 proposes cutting biologics exclusivity from 12 to 10 years. That could open up the market for cheaper versions of drugs like Humira and Enbrel sooner.

And globally, the WTO is debating whether to waive exclusivity for more drugs beyond COVID vaccines. If that happens, it could change how long companies can protect their drugs in the U.S. and abroad.

By 2027, experts predict regulatory exclusivity will account for more than half of all market protection time for new drugs-surpassing patents. Why? Because patents are getting weaker. Courts are striking down secondary patents. But the FDA’s exclusivity rules? They’re still standing.

What to Watch For

When a new drug launches, check two things:

- Is there a patent? Look it up in the FDA’s Orange Book.

- Is there exclusivity? Check the FDA’s Exclusivity Dashboard.

If the patent expires but exclusivity is still active, don’t expect generics. The drug will stay expensive. If there’s no patent but exclusivity is active, the same thing happens. And if both are gone? That’s when prices usually drop-fast.

For patients, this means asking your pharmacist: "Is there a generic available?" If not, ask why. The answer might surprise you.

For manufacturers, it means understanding both systems. Don’t assume a patent is enough. File for exclusivity. Don’t miss deadlines. Don’t assume the FDA will catch your mistake. You’re responsible for claiming it.

And for policymakers? The system was designed to balance innovation and access. But today, it’s tilted too far toward protection. The average drug earns 65% of its total lifetime revenue in the first year after approval. That’s not innovation-it’s monopoly pricing.

Does a patent guarantee that no generic can enter the market?

No. A patent gives you the legal right to sue someone who copies your drug, but it doesn’t stop the FDA from approving generics. If a generic company files an application and proves the patent is invalid or not infringed, the FDA can approve it-even if the patent is still active. Market exclusivity, on the other hand, is enforced directly by the FDA. If exclusivity is active, the FDA won’t approve any generic, no matter what the patent says.

Can a drug have market exclusivity without a patent?

Yes. In fact, that’s common. For example, colchicine had no patent but received 10 years of market exclusivity because the company submitted new clinical data for a new use. Orphan drugs, biologics, and drugs with pediatric exclusivity can also get protection without any patent at all. The FDA doesn’t care if the drug is new-it cares if you did the studies to prove it’s safe and effective for a new purpose.

How long does market exclusivity last for a new drug?

It depends on the type of drug. A New Chemical Entity (NCE) gets 5 years. Orphan drugs get 7 years. Biologics get 12 years. Pediatric exclusivity adds 6 months to whatever other protection exists. The 180-day exclusivity for the first generic challenger is separate and only applies to one company. These periods can overlap with patents, but they don’t depend on them.

Why do some drugs cost so much even after their patent expires?

Because market exclusivity may still be in effect. For example, Trintellix’s patent expired in 2021, but generics couldn’t launch until 2024 because of 3 years of FDA exclusivity. Also, companies sometimes use "product hopping"-making small changes to the drug and getting a new patent or exclusivity. And if no one challenges the exclusivity or patent, generics never come in, and prices stay high.

How can I find out when a drug’s exclusivity ends?

The FDA’s Exclusivity Dashboard, launched in September 2023, lists all active exclusivity periods for approved drugs. You can search by drug name and see exactly when exclusivity expires. It’s public, free, and updated in real time. Pharmacists, insurers, and generic manufacturers use it to plan ahead.

so like... the fda just gives out monopoly rights like candy? no patent needed? how is this legal? they're just letting pharma companies charge $5 for colchicine like it's a new invention? i think this is all rigged. someone's getting rich off this and it ain't us.

This is precisely why Ireland’s healthcare system is collapsing. The FDA’s regulatory capture is a disgrace. These so-called exclusivities are not protections-they’re corporate welfare dressed up as innovation. If you can’t innovate, you shouldn’t be allowed to profit. The 12-year biologics monopoly? A national scandal.

Let’s be real-the entire pharmaceutical industrial complex is a Ponzi scheme built on regulatory arbitrage. Secondary patents? Patent thickets? Pediatric exclusivity for drugs never tested on children? It’s not innovation. It’s legalized extortion. The FDA isn’t a gatekeeper-it’s a concierge for Big Pharma. And we’re the ones paying the tip.

This is actually super helpful! I never realized how much of this was hidden in plain sight. I’m gonna start checking the FDA dashboard before I fill any new scripts. Knowledge is power, y’all 💪

I work in pharmacy and this is spot on. Patients get so mad when they can’t get a generic and don’t know why. The exclusivity thing is the real villain. Patents get all the attention but it’s the FDA’s clock that really locks them out

The FDA dashboard is a game changer. I’ve been tracking a few drugs for my mom’s prescriptions. Found out one’s exclusivity ends next month-went ahead and called her doc to prep for the switch. 🙌

The term 'market exclusivity' is a euphemism for regulatory rent-seeking. The Hatch-Waxman Act was designed to balance innovation and access. What we have now is a system where litigation costs are externalized onto taxpayers while private entities capture 90% of the surplus. The economic inefficiency is staggering.

THEY’RE LYING TO US. THEY’RE LYING TO EVERYONE. PATENTS ARE A SMOKESCREEN. THE FDA IS A CORPORATE TOY. THIS ISN’T HEALTHCARE-IT’S A FINANCIAL ENGINE THAT KILLS PEOPLE TO MAKE PROFITS. I’M NOT JUST MAD-I’M TERRIFIED.

You’re all missing the point. The real issue is that no one’s holding the FDA accountable. They approve drugs with dodgy data, then grant exclusivity. Then the companies jack up prices. It’s a feedback loop of greed. And we’re the fuel.

I’ve been watching this for years. I know people who died because they couldn’t afford their meds. I know people who had to choose between insulin and rent. This isn’t policy-it’s murder by bureaucracy. And they call it 'innovation'. I’m done pretending this is fair.

The empirical data indicates that regulatory exclusivity, particularly in the context of biologics, constitutes a significant barrier to market entry for biosimilars. The 12-year period, as currently structured, demonstrably reduces price elasticity and impedes cost containment objectives. A reduction to 10 years, as proposed by the PREVAIL Act, would yield statistically significant savings without materially impacting R&D incentives.

So let me get this straight… the FDA gives a 10-year monopoly on a drug that’s been around since ancient Egypt? And you’re surprised people are angry? 🤡